|

Men Behaving Badly

Feature and interviews by Carlo Cavagna

|

| |

|

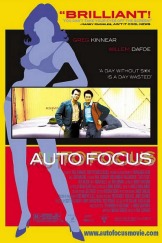

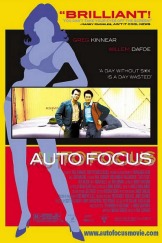

Auto

Focus |

USA, 2002. Rated R. 104 minutes.

Cast:

Greg Kinnear, Willem Dafoe, Rita Wilson, Maria Bello, Ron Liebman, Bruce

Solomon, Michael Rodgers, Kurt Fuller

Writer: Michael Gerbosi, based in part on the book The Murder

of Bob Crane, by Robert Graysmith

Director: Paul Schrader

|

|

|

Roger

Dodger |

USA, 2002. Rated R. 105 minutes.

Cast:

Campbell Scott, Jesse Eisenberg, Isabella Rossellini, Jennifer Beals,

Elizabeth Berkley, Mina Badie

Writer: Dylan Kidd

Director: Dylan Kidd

|

• Carlo's

review of Auto Focus • Carlo's

review of Roger Dodger

• Related

materials and links

n

cinema's Golden Age, everyone understood what qualities made a man. Heroes were

strong, self-assured, and irresistible to the ladies--even if the ladies didn't,

at first, realize it. Now, men in the movies are complicated. The old stoic

male ideal does still have appeal, or Russell Crowe wouldn't have won an Academy

Award for Gladiator; but a growing number of today's films deconstruct

the old values and question what it is to be a man. Two such films are Auto

Focus and Roger Dodger, released in theaters in October. Roger

Dodger probes the mystique of the suave womanizer--the kind of guy many

men wish they could be--while Auto Focus goes behind the affable family

man façade of a popular television hero.

n

cinema's Golden Age, everyone understood what qualities made a man. Heroes were

strong, self-assured, and irresistible to the ladies--even if the ladies didn't,

at first, realize it. Now, men in the movies are complicated. The old stoic

male ideal does still have appeal, or Russell Crowe wouldn't have won an Academy

Award for Gladiator; but a growing number of today's films deconstruct

the old values and question what it is to be a man. Two such films are Auto

Focus and Roger Dodger, released in theaters in October. Roger

Dodger probes the mystique of the suave womanizer--the kind of guy many

men wish they could be--while Auto Focus goes behind the affable family

man façade of a popular television hero.

Auto Focus is the latest from director Paul Schrader, screenwriter for

some of Martin Scorsese's finest films--Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and

The Last Temptation of Christ. All are centered on a protagonist tortured

by his dual nature, a man struggling between what he is and what the world expects

him to be. Schrader's other screenplays (e.g., The Mosquito Coast, Patty

Hearst, Obsession) and directorial work, particularly Affliction,

are woven from the same thread. "[The] kind of clueless guy, the unreliable

narrator who thinks he is one thing but in fact is another--he's acting in a

manner that is counterproductive to his own desires. I love that character.

I've fooled around with that character a lot," remarks Schrader.

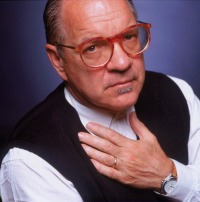

Auto Focus

director Paul Schrader |

The life of television star Bob Crane (Greg Kinnear) of Hogan's Heroes

(1965-1971 on CBS) does not at first glance seem like fertile ground for Schrader.

Yet after Crane was mysteriously killed in a Scottsdale, Arizona, motel room

in 1978, his secret life emerged--not that he kept it much of a secret after

his divorce from his first wife (Rita Wilson). An amateur pornographer, Crane

had sex with hundreds of women and documented every encounter with photographs

and video footage, using some of the first video cameras on the market. His

partner in these sexual escapades, video technician John Carpenter (Willem Dafoe),

became the prime suspect in the murder, but accumulating evidence was difficult.

Carpenter was finally tried in 1992, but acquitted.

|

In June 1978, Hogan's

Heroes star Bob Crane was murdered in a motel room in Scottsdale, Arizona,

where he was performing his touring dinner theater play, "Beginner's Luck."

The Scottsdale police accumulated insufficient evidence to indict their

prime suspect, Crane's friend John Carpenter. Finally, in 1992, the County

Attorney brought a case against Carpenter, but Carpenter was acquitted.

Question: Who killed

Bob Crane?

Bob Crane, Jr.: For

a while, I thought it was John Carpenter, but I go to that fine show,

C.S.I. They should have been there… It would have been solved.

Motive, opportunity, and access, I think is what they say. I really think,

out of everybody involved, that my stepmother had motive, access, and

opportunity… No one gained anything from my dad's death except my stepmother.

They were going through an ugly divorce at the time of his death. I was

living with my dad in an apartment in Westwood… The marriage was over.

She had come into Scottsdale ten days before he died, on Fathers Day,

with Scotty [Crane], her son, seven years old [at the time]. They came

into Scottsdale unannounced, more or less a knock at the door… They're

going through an ugly divorce. This is the last person who should show

up. Ten days later he's dead.

There were three keys to

the apartment. My dad had one, [his co-star in the play] had one, and

there's a third key, which I think Patti had. The only person that gained

anything financially from this whole thing is Patti. She lives in a nice

house on Bainbridge Island in the state of Washington. She and her son

Scotty have started a Web site--it's a year old now--which sells his material,

his private personal material, to make a buck… This doesn't show to me

any great love. This is the widow expressing her love for her late husband

by showing and selling X-rated videos and stills on a Web site? Something's

wrong with this picture.

Paul Schrader: Scotty

thinks Bobby Crane, Jr., was the one. [laughs] And Bob Crane, Jr.,

impugns the paternity of Scotty, and Scotty impugns the paternity of Bob

Crane, Jr… Historically Carpy [Carpenter] is the best fit. Scottsdale

Police believed it; Scottsdale D.A. believed it. They took him to trial.

He had means, motive, opportunity. They just didn't have much evidence.

The jury was out twenty minutes. If I was on that jury, I would have voted

to acquit as well. But I still think he's the best fit, the number one

suspect. All the other suspects have many more problems than Carpy, and

that's just speaking historically. Speaking dramatically, he's the only

fit. I don't know if you have a movie if Carpy didn't do it.

Maria Bello: I think

there's a lot of infighting with those families. Who the hell knows what's

going on.

---------------

Question:

Patti Olson (Crane's second wife) and Scott Crane (Crane's son by Patti)

have publicly condemned Auto Focus and criticized its accuracy.

Could you comment?

Bob Crane, Jr.: Scotty

and Patti wrote their own script. I heard it was awful. God knows what

that looked like, because they're revisionists. They rewrite history,

as they have on their Web site… Patti says, for instance, that she and

my dad reconciled in April of '78. Well, if they did, why in June of 1978

was I still living with my dad in Westwood, California, in an apartment

and he was going through a divorce with her? So, they took their script

around. They shopped it around; it was awful; nobody wanted it. That's

the end of that. Then they see that Paul Schrader is going to do a film

called Auto Focus, and that completely torpedoes their script.

Naturally, they wanted their script to be made, not somebody else's script.

So they've never been on board this project.

Schrader: To understand

Scotty's situation, you have to back up about a year. Scotty wrote a script

with his partner called Take Off Your Clothes and Smile. That script

was not made. He couldn't get it made. They felt that whatever script

should be made, they (they being he and his mother Patricia) should

control. I was told…at that time, "Stay away from these people. They want

to control this movie. If you meet with them, they'll say you took their

script." So I didn't get involved with it until I was already shooting…

Out of that initial grievance…a lot of other grievances have flowed, including

some rather peculiar ones that might be fixations of his, if you know

the Web site, about penile size and so forth. I know for a fact from people

who have read his script that his script is really quite nasty about his

father, too. So, I have to believe that the true issue is this power issue,

and not the portrayal issue. You have to bear in mind, Scotty is also

the one who's putting the porn on the Web. He feels that this is what

his father would have wanted. I'm not sure about that. I'm not if Bob

would have wanted those photos on the Web. So, we'll see where this goes.

They have said they'll sue us. Sony's a big company with a lot of lawyers,

and they have vetted this motion picture to a millimeter of his life.

Sony's willing to stand by it. So I don't know how far they can get with

this lawsuit.

Willem Dafoe: I don't

think this movie is a biopic… We take the facts and we create a fiction.

I'm not sure there's such a thing as a real movie--a movie that's true.

It's always fiction, right? Because it's removed that one time. So, you're

responsible, but you can't be totally saddled by that, because you gotta

believe that the power of the fiction will release you to be able to maybe

find some sort of truth that goes beyond the facts…which is a lot of double-talk,

but you get the idea. I do believe in it.

Paul Schrader: You

have to have both. You have an obligation to history, to portray these

events with a reasonable authenticity. You can never know what actually

happened. Even people who were at the same meeting have different versions

of what happened. Then you have another obligation to the needs of drama,

to have a certain character arc and a certain ebb and flow of events.

If you do it right, you can meet both needs. And if you can't meet one

need without short-shifting the other, then you need to rethink doing

the thing at all.

|

Crane had married early and plugged away for years at a showbiz career before

he landed the title role in Hogan's Heroes. He became a household name,

and women offered themselves to him freely. He was unable to resist, and soon

pursued women actively. Beneath the wholesome, self-assured image of Hogan was

a troubled man who succumbed to a compulsive desire for sex, stunting his career

and probably leading to his demise.

Superficially, Crane's story seems the old cliché about the celebrity who couldn't

handle fame. But the fact that he was a celebrity raises another issue for the

movie to explore. As his portrayer Kinnear muses, "Where does the ability to

act on people who make themselves available to you run into addictive behavior?"

In Crane's case, he had been obsessive long before his fame. Kinnear relates

how Crane's eldest son, Bob Crane, Jr., showed him a log Crane kept of the family's

Sunday water polo games. "They would all get into the pool and play water polo,

and Bob would keep these ledgers of how many shots on goal Bob had against his

sister, and who scored the most points, and what the final outcome of the water

polo game was. The obsessive nature of the man was starting to rear its head

early." Bob Crane, Jr., served as a technical consultant, contributing tips

on set design and dialogue (in particular Crane's odd remarks on the color orange),

and appears in the film as an interviewer for a Christian publication.

Obsession and Crane's inability to reconcile his role as a family man to "normal"

male behavior are at the core of the film, even though Schrader, Kinnear, and

Dafoe are unanimously quick to point out the existence of several other thematic

strands--the birth of porn, the corruption of celebrity, and the co-dependent

relationship between Crane and Carpenter. There's also the story of Hogan's

Heroes, a successful situation comedy about Allied soldiers in a German

POW camp that was recently named by TV Guide as one of the fifty worst

TV shows all time. Schrader and the cast reproduce the show faithfully. Kurt

Fuller, who plays Werner Klemperer, watched hours of shows, and does a spot-on

impression of Klemperer's Colonel Klink.

Maria Bello, who appears as Crane's second wife Patti Olson (stage name Sigrid

Valdis), found another source of inspiration. "One of my agents…was watching

the Game Show Network at night, and saw an old Dating Game with Patti

Olson and Bob Crane. So I have this Dating Game tape of them interacting

as a couple, and she's going like [dismissively], 'Oh, Bob.' I took a

lot of my character later in life, toward the end of the movie, from the tape--from

how I saw how she was with him. She seemed tolerant but over him."

Though the story of Hogan's Heroes is told, it remains secondary. As

Kinnear observes, "The fact that it was Bob Crane would not have been an interesting

enough handle to make this movie. If Bob Crane had been an insurance salesman,

I still would have been interested in the role because of what it was dealing

with, and all of the different components of behavior that comprised this guy,

and the self-morality that he seemed to have. The one-woman family-man element

combined with his lascivious documentation of all his liaisons was much more

interesting to me than anything."

Greg Kinnear.

|

Kinnear, best known for comedic roles, seems a counterintuitive choice for

a man as complicated as Crane. Kinnear concedes, "It certainly was a different

role for me, but the roles you might be used to seeing me in are partly an element

of my own choices, but also an element of what opportunities you get. There

is a compartmentalization with actors. I've done a lot of light comedy, and

people are comfortable with that. I haven't set out on some great trek to discover

some dark side. I am trying to evolve as an actor, and try different kinds of

roles, and this fit the bill." He stands by his previous work, though. "Comedy

gets a bad rap. It's rarely recognized, and people [just say], 'Aw, well, they're

just having fun!' But every job has its own demands."

Kinnear turns out to be a perfect fit for Crane's public persona. "I never

considered anybody else," says Schrader. Schrader wanted Kinnear because he

knew Kinnear could handle Crane's lighter side, which is not his own forte.

"That's hard stuff to do. And I'm real comfortable on the deep end of the pool.

I know how to get an actor out in the deep end, turn the lights off, and makes

sure that he reaches the shore. So I figured Greg would protect me on the shallow

end, and I'd protect him on the deep end."

One might think that Crane's lack of introspection would make Kinnear's work

easier. Because Crane was oblivious to the damage he caused to himself and those

around him, not a lot of acting fireworks were required. Crane was simply a

guy who didn't get it. "Sex is normal," he says in the movie. Yet shallowness

brought its own problems. "I think that one of the toughest elements to Bob's

persona is his unawareness of the damage he's doing to himself and the people

around him, and incorporating some sort of lack of self-introspection," says

Kinnear. "It's exactly what you don't want to do as an actor. You're

always trying to create characters that are aware and are making choices and

are following their instincts, and with this kind of role, you had to toss all

that shit out, and just go with this obliviousness that Bob seemed to have.

Making matters more difficult for Kinnear was the tight one-month shooting

schedule and the fact that Crane appears in virtually every scene. Kinnear,

usually a supporting actor, was not used to that. "Certainly this was more difficult

than some of the previous work I've done, primarily because of the amount of

work. I've done a lot of supporting work, where you pop in for two or three

days during the week and go hunt ducks or something, and this was all week long,

all day long. Because it was a short shoot, and there were financial limitations,

we were shooting Bob at fifty, followed by Bob at thirty-two, followed by Bob

at forty-one. That was tricky for me." So how did Kinnear keep track of where

he was in the evolution of his character? "A good script supervisor, and my

own awareness. I spent a lot of time making sure I knew where I was in the story.

It wasn't as important as to where I was going in the story when I did a scene--because

obviously Bob wouldn't know where he's going before he gets there! But certainly

where I [am] coming from helps inform me. Some actors don't even care. They're

just in the moment, they just do the work right then, regardless of where they've

been or where they're going. For me, it helps knowing where I'm coming from.

But, you also try not to carry that cross too heavily or you can end up manipulating

the performance too much."

Because Crane was clueless, Schrader resorted to dream sequences, metaphors,

and symbols to get at his inner life. "Crane was not an introspective man. There

were no dark nights of the soul in the Crane house. So you have to get at these

problems of his in a kind of glib way. So you have the breast montage with his

chipper, 'Tits are great!' sort of like, 'Sugar Pops are tops!' Then you have

the dream sequence, which is his crisis of his first marriage, which is handled

as a surreal experience on the set [of Hogan's Heroes]. My thinking in

that was that because Crane was not a deep person, you have to be playful about

this as well."

Kinnear may be an unexpected participant in a Schrader project, but Dafoe is

not. He and Schrader have collaborated numerous times. In addition to The

Last Temptation of Christ, he's appeared twice before in Schrader-helmed

films, Light Sleepers and Affliction. Schrader explains, "Obviously

the more you know somebody and work with him, the easier it becomes. Willem

is also a friend… But, in terms of Willem as an actor, I know that some directors

like Willem when he gets outrageous and angry. I tend to like Willem when he's

vulnerable and needy. I've tended to cast him as a weak person. I think he has

a lot of interesting colors on that end of the spectrum."

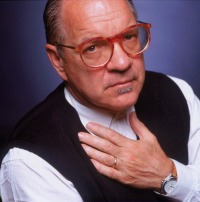

Willem Dafoe |

For his part, Dafoe is attracted to Schrader's work because, "I like the way

he thinks; I like the way he tells his stories. I like his passion, which is

expressed in an aesthetic that isn't always seemingly passionate. It's a little

cool; there's a little distance there. And I think you can receive the resonances

of the story better. He's not a gratuitous guy. He deals with matters of the

flesh and the spirit in a lot of his stories, but they aren't movies that are

all hammed up, where you get juiced up and don't have any perspective on it…

We've developed a shorthand. He knows me; I know him. He gives me interesting

opportunities. We work fast. He does a lot of his work in the screenplay, in

the design, and in the casting. When we get [on the set] he's quite pragmatic…

So, you respond to that kind of efficiency, that kind of communication. But

above all, I think he still struggles in a creative way with…themes I respond

to, because I do often find myself attracted to dark stories… Ironically, I

feel more uplifted by these dark stories, because sometimes if the story is

told sincerely and passionately, you find compassion in unexpected places, and

you leave the theater with the feeling of a shift of thinking that I always

like."

Commenting specifically on what attracted him about Auto Focus, Dafoe

says, "This movie ends up not being about what it seems to be about--like most

good movies. Moby Dick is not about a whale… One of the things that attracted

me about the screenplay was there were scenes that were like domestic scenes,

but domestic scenes that are usually played between a man and a woman. Yet,

they weren't homosexual scenes, yet they were tinged with sexuality. Those are

interesting mixes… [Auto Focus] is not just about behavior. It's about

the strategies of how people live, and where they seek their happiness and how

they engineer their lives to try to feel good. If we all feel like we need something,

like we're a little incomplete, that's where John Carpenter is a tragic figure,

because he needs Bob. He's a very needy guy… He has to attach himself to Bob

Crane."

|

Two-time Academy Award

nominee Willem Dafoe is one of the most respected American actors, and

is known for his discipline and preparation.

Question: How do

you prepare for a role?

Willem Dafoe: It's

always a combination of things. Research. You take whatever's available

to you, particularly when you're playing a character that's based on a

real-life character. And then you do whatever you feel like you need to

do. Sometimes it's learning a skill. [For Auto Focus], I could

have thrown myself into the technology of those early video machines.

To tell you the truth, I didn't feel the need. I felt the need to know

only as much as I had to perform in a scene. I always feel like you take

whatever helps you to pretend, to feel the authority to pretend. And sometimes,

when you grab stuff that you don't need, it creates a clutter. It creates

a responsibility to details and things that obscure what you're really

talking about.

This movie is not about

video cameras. But, at the same time, in order to play the scenes and

feel confident enough not to fall out of the scene, to be holding the

video camera with some kind of authority and ownership, you have to know

enough about it to have that happen. So, you're always walking a line,

but you can always ask yourself, "What do I need? What do I need? What

do I need to feel like I can inhabit that character?" It's always a mix

of things… It's moronically simple in a way, because if you look at the

script, you see what the character has to do. You have to know how to

do those things, and do them well. Particularly if it's a specialized

profession--you learn that profession because it colors the action so

much.

|

Auto Focus exaggerates the amount of time Crane and Carpenter spent

together, making them seem inseparable. Schrader defends the decision because

he identifies the mutually enabling relationship as the dramatic crux of Crane's

story. Crane needed Carpenter for the video equipment; Carpenter needed Crane

for the access to the women. Without the other, each man might have lived his

life in a different way.

Roger Dodger

director

Dylan Kidd |

Unlike Schrader, Roger Dodger's Dylan Kidd is a first-time feature writer

and director. Auto Focus covers a lifetime; Roger Dodger transpires

in about one day. Yet the pictures share thematic similarities. In both films,

women come and go while the obsessive protagonist reveals himself as a twisted,

insecure man whose perception of himself could not be further from the truth.

In Roger Dodger, a thirty-something New Yorker, Roger (Campbell Scott),

takes his visiting teenage nephew Nick (Jesse Eisenberg from Fox-TV's Get

Real) under his wing to teach him how to score with women. Buying into the

idea that the man should be in charge, Roger is driven to assert control over

women. He sees himself as a self-assured, suave ladies man who has women all

figured out. The first hint of Roger's underlying problem is in the opening

conversation, in which he argues that men need to maintain dominance in order

to stave off their growing irrelevance as breadwinners and reproductive partners.

Roger feels threatened by the changing roles of men and women in the contemporary

world.

Kidd identifies the initial inspiration for Roger as an old college classmate,

who would hit on women by finding their weak points and attacking them. Kidd

describes Roger as a blowhard. "The phrase I always had associated with Roger

was 'smoke and mirrors.' I just thought, this guy should be chain smoking. He's

literally blowing smoke, and you have to fight through the smoke and all the

words. He doesn't want anyone to really see him. So he's literally antsy and

dodging, and I thought 'Roger Dodger' would be a perfect nickname for him… And

the camera is expressing that thing too. The movie, visually, is meant to feel

very restless, like this guy who's not comfortable in his own skin." However,

Kidd also notes, "The movie would fail if at any point you feel like he's physically

threatening." Roger is just a talker.

As in Auto Focus, a key point of tension is whether the protagonist

will ever gain self-insight. The story is catalyzed by the arrival of Roger's

naïve nephew, who wants to know how to talk to the girls at his school. Kidd

explains, "Nick is definitely the key… I think when Nick shows up, people are

like, 'Oh, okay, this is the hook of the movie. We know this guy is the last

person he should be asking advice on dealing with women.'"

Dylan Kidd on

the set |

Like Kinnear, Scott is a counterintuitive casting choice. Because Scott has

played mostly nice guys in movies like Longtime Companion and Singles,

not even Kidd had considered him for the role. It was only by purest chance

that Scott was cast and that the film was even made. Kidd, who had no financing

and no cast apart from Eisenberg, remembers, "I was sitting in a coffee shop

and Campbell Scott walked in… I sat and watched him for about ten minutes. I

thought back on his career and said, 'This guy's a great actor. And he's somebody

who takes chances with first time directors…' I really liked him in The Daytrippers…

He was very much part of getting that movie made… That's a movie where he plays

a bit of a womanizer… Usually they just make him into--I don't know, I enjoy

David Mamet, and I liked The Spanish Prisoner, but that's Campbell being

very pulled back. He's got real charisma."

Scott promised to read the script Kidd thrust at him. To Kidd's surprise, Scott

kept his word. Why did Scott get behind this project when most actors would

have refused even to accept an unsolicited script from a stranger? Jennifer

Beals has a theory. "Campbell is a god."

For Beals, a phone call from Campbell was all it took to get her on board,

script unseen. "If Campbell had said, 'I have this part where you stand on your

head for two hours,' I would have said, 'Great! I can't wait!' I would have

practiced standing on my head after the phone call... If I had to choose one

leading man for the rest of my life, it would be Campbell Scott. Period."

|

Roger Dodger was filmed

in Manhattan in October 2001, shortly after the terrorist attacks on the

World Trade Center of September 11th.

Question: What was

it like filming in New York immediately after 9/11?

Berkley: Oh god.

I was here in LA at the time it happened, and I was glad that they were

going ahead, because even though everything seemed kind of trivial and

you felt kind of felt guilty for doing anything, at the same time,

at least doing something creative helped the city… This was a real New

York movie, and something that maybe could help employ people who needed

jobs at that time. We got a lot of crew that we would never get, because

people needed to work. They needed to work not just for money, but needed

to work--for their soul. To put it somewhere. It was like their salvation

at the time. So there's a real amazing energy… Everyone was very close.

It was a really special experience.

Beals: What's fascinating

to me is that there's this whole theme that goes on in the film about

innocence versus experience. You think that you could be watching the

typical coming-of-age story, where you watch innocence move into experience.

And truly…the story is…this guy who's cynical and abrasive and world-weary

[finding] his way back to innocence. To be shooting that kind of story

in Manhattan right after September 11th was…unbelievable. It was incredibly

difficult, incredibly moving… I think because the whole country and the

city itself were trying to make the same journey--because the city and

the country had been so brutally robbed of [their] innocence… We

were all trying to make our way back to, 'How do we live our lives now

with joy and hope and some kind of vibrancy and vitality, without this

innocence? How do we find that again?' So, to me, it was a really extraordinary

time. Painful, but extraordinary. And we were all very lucky… People were

trying to find a place to express their grief, and express their feelings,

and we were incredibly lucky as actors and technicians to be taking part

in a story that let us express ourselves. It was a healing time for us

all, I think.

|

Beals remembers how Scott came to her rescue during the filming of Mrs.

Parker and the Vicious Circle. "I was really nervous because I going to

work with Campbell and I was going to work with Jennifer Jason Leigh, and you

know, it's Alan Rudolph. It was my first scene…and I went up on a line. It felt

like an eternity, and finally I…got the line out." Rudolph didn't notice. "I

was so humiliated. I just felt so terrible, and I went into the corner-literally--and

thought I was going to have a nosebleed or some form of a nervous breakdown."

Campbell looked at Beals for a moment without saying anything, then approached

Rudolph to ask for another take, insisting that he had himself botched his line

delivery. Rudolph finally assented. "There is an altar to Campbell Scott in

my house with a candle burning at all times," kids Beals.

By virtue of a string of coincidences, Beals and Elizabeth Berkley, who play

best friends and test subjects for Nick's "training," received the script at

virtually the same time through different avenues. The coincidences don't stop

there. Both Beals and Berkley have dance training; both starred in high-profile

sex symbol roles that involved dancing (Flashdance and Showgirls,

respectively), and both struggled with their careers afterward. Each rebuilt

her career slowly in independent films, though Berkley still takes the odd supporting

role in big-budget productions. Berkley's name is still greeted with skepticism

in the film industry, as Kidd testifies. "I was willing to meet with her, but

I was skeptical, like a lot of people probably are. But she's incredible. She's

a wonderful person, and her frustration, I think, is that she just needs to

get herself into the room… If she can just get into the room there's nothing

she can't do."

In the film, Beals and Eisenberg share a brief kiss, a tender one despite their

age difference. Eisenberg was born in 1983--the year Flashdance was released.

He has yet to see it (though he does confess to watching Saved by the Bell).

Regarding the kiss, Eisenberg remarks, "It's bizarre… It crosses the line of

no longer acting--you're really kissing. You're not faking it. Everything else

you're faking. Conversation, you're mad at them, you have an argument with them

in the script, and they say, "Cut"--you didn't really have an argument with

them. But you really do kiss someone. It's like nudity--it's final."

Both Roger and Bob Crane are difficult protagonists with whom to sympathize,

but they are consistently unusual, and thus, interesting. Though they never

become likable, gradually their souls are laid bare. However, both Schrader

and Kidd refuse to moralize overtly, preferring to communicate their perspective

more subtly. As Kidd says, "It's impossible to take this kind of movie and tie

it up with a bow."

Instead of being male ideals, both men are pathetic, acting out male fantasies.

Instead of wrestling with their demons, they attempt to feed their egos and

fill their emotional emptiness with sex. As Bello observes, "When you get beneath

the veneer of anyone, you see so much more than you bargained for… We all have

our darkness, right? We all have our darkness that we have to deal with--the

things we don't like about ourselves, whatever they are." Both movies can be

seen as ultimately advocating self-knowledge as the best way to cope with the

world, as opposed to clinging to outmoded and destructive ideals for male behavior.

Ultimately, Kidd thinks men are exploring their changing roles reluctantly,

and not always successfully, but doggedly, and reaching the same conclusions

most people always have. "I think men are at a challenging point in their history

right now, in that a lot of their traditional roles are no longer there… I think

it takes a special guy these days to not fall back into either macho posturing

or weepy, new agey [behavior]. It's tough to find a middle ground. For me what

[Roger Dodger] is about, at its core, is this very male idea that there's

a right way to do something, or that there's a strategy that will help you win,

when in fact life is about being in the moment and just trusting your gut. Both

these characters have to learn that. Nick is at that age where you think, somebody

out there has the secret. If he can just get the answer, he'll be fine. And

Roger feels that he has the answer. They're both wrong. The answer is

you have to make your own way through life. Despite what the culture tries to

tell you, there's no rules, and there's no right way to do it."

• Carlo's

review of Auto Focus • Carlo's

review of Roger Dodger

Feature and interviews

© November 2002 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images © 2001 Sony Pictures Entertainment, Inc., and Artisan Entertainment.

All Rights Reserved.