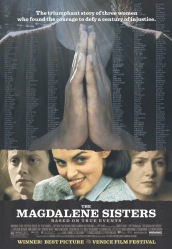

Peter Mullan's new film, The Magdalene Sisters. |

Profile and Interview:

Peter Mullan

by Carlo Cavagna

|

by Carlo Cavagna

|

||

![]() cottish

actor Peter Mullan's latest directorial effort is winning prizes and upsetting

the Vatican. The Magdalene Sisters is an exposé of the Magdalene

Asylums in Ireland, where as late as the 1970s women were locked up for sexual

transgressions (like having children out of wedlock) and forced to provide slave

labor in the Asylums' laundry businesses. The movie opened this year's Venice

Film Festival by having its screenings picketed by Catholic priests, and closed

it by taking home the Golden Lion and three other awards. However, it is as

an actor that Mullan has made name for himself, in defiance of cinema having

little use for working class Scots with impossible-to-conceal Scottish brogues.

(Sean Connery may have a Scottish accent, but Peter Mullan really has

a Scottish accent.)

cottish

actor Peter Mullan's latest directorial effort is winning prizes and upsetting

the Vatican. The Magdalene Sisters is an exposé of the Magdalene

Asylums in Ireland, where as late as the 1970s women were locked up for sexual

transgressions (like having children out of wedlock) and forced to provide slave

labor in the Asylums' laundry businesses. The movie opened this year's Venice

Film Festival by having its screenings picketed by Catholic priests, and closed

it by taking home the Golden Lion and three other awards. However, it is as

an actor that Mullan has made name for himself, in defiance of cinema having

little use for working class Scots with impossible-to-conceal Scottish brogues.

(Sean Connery may have a Scottish accent, but Peter Mullan really has

a Scottish accent.)

Peter Mullan appears in a cameo in his new feature film, The Magdalene Sisters. |

Rejected by the National Drama School and with a tendency to work himself to exhaustion, Mullan devoted his twenties to university studies and teaching drama. Now forty-nine years old, Mullan did not begin appearing in movies until his mid-thirties, making his film debut in 1990, with tiny roles in The Big Man (with Liam Neeson) and Ken Loach's Riff-Raff. For the next several years, Mullan continued taking bit parts in movies made or set in Scotland, including Braveheart (as the guy who says Mel Gibson is too short to be William Wallace), and Danny Boyle's Shallow Grave (as a thug) and Trainspotting (as a drug dealer). At the same time, he was developing his filmmaking skills with projects like the short film Close.

Mullan got his big break in 1998, when Loach cast him as the lead in My Name Is Joe. His performance was hailed as nuanced and naturalistic, and earned him the Best Actor prize at Cannes. At the same time, Mullan's feature directorial debut, Orphans, was winning a number of minor awards at various European Film Festivals. The story of four siblings who gather to mourn their mother prior to her funeral, Orphans was also successful with many American critics. My Name Is Joe led to lead roles in larger pictures, including Ordinary Decent Criminal with Kevin Spacey and Linda Fiorentino, Mike Figgis' Miss Julie, and Michael Winterbottom's The Claim, a Western retelling of Thomas Hardy's The Mayor of Castorbridge. In the latter film, Mullan's riveting performance as the brooding Daniel Dillon was the only reason to watch, standing out of a cast that included Sarah Polley, Wes Bentley, Milla Jovovich, and Nastassja Kinski. Mullan also distinguished himself as the desperate, troubled owner of an asbestos removal company cleaning an abandoned mental institution in Brad Anderson's excellent indie horror picture Session 9, also with David Caruso and Josh Lucas.

Now Mullan has brought The Magdalene Sisters to the United States, and is eager to promote his film. Inspired by a documentary, the film deals with what he feels is deeply important subject matter. Talking to reporters in Los Angeles in July 2003, the genial, garrulous Scotsman had a lot to say about making his film, the history of the Magdalene Asylums and the Catholic Church, and his own nervous breakdown. [Read the review]

Question: In the two weeks in Italy leading up to the prize at the Venice Film Festival, your film was the subject of incredible counter-attacks by the Vatican. The Vatican sent priests to the screenings with camcorders to tape moviegoers and say to them, "We know who you are; you're going to hell for this." How did the moviegoers react? What did they do?

Mullan: Oh, they just went and they didn't give a shit. They're weren't impressed by that kind of antic. That was just absurd. Hi-tech Spanish Inquisition—how dumb is that? No, the Italians paid no attention. When you walked around Venice, you got an indication of how the film was going by the number of people, particularly women, who go by and go, "Bravo! Bravo, Moo?lan!" It was all done with a fervor, and at first I missed the "Bravo!" I just heard the "Moo-lan!" It was like, "Whoa. Maybe they don't like the film very much." Then, as it went on, I'm quite literally walking around Venice [with] people jumping out at me who had seen the public screening. It was really heartfelt. It wasn't so much revelatory to them what happened in Ireland, it was more that they felt that they had something to hoist up the mast, as it were, to display their own frustrations. As far as I'm aware, there were no Magdalenes in Italy. [But] in terms of the Catholic Church's treatment of women over the years, there was obviously a real frustration on their part.

Question: How did you come across this story?

Mullan: The story I saw was a documentary called Sex in a Cold Climate on Channel Four [a UK television network], just before I went to Cannes with My Name Is Joe and Orphans. It was mainly talking heads, and most of the women, by the time I saw the documentary, had passed away. Most of the women who spoke had been diagnosed as having a terminal illness. When Steven Humphries, who made the documentary, first went looking for women to talk about their experiences, the women came forward in the knowledge that if they didn't, then they would go to their graves with that particular injustice, that story, untold. So that's how I came across it. And that's what really moved me to want to do something about it, because the documentary didn't have a happy ending. They didn't go off and find a good life for themselves. They hadn't been given any recognition. There had been no justice. There had been certainly no justice as regards to the babies who had been taken from them.

So part of the motivation to make it was that one might be able to raise public awareness that then might put pressure on the Church to start doing, for want of a better word, the right thing, and apologize in action as much as in words. Most important to the women I've met is a genuine apology. They're not interested in a written apology. They want a genuine act of contrition on the part of the Church, so they can go back to Mass. That's the big thing. They're all at a certain age. They want to go back to the Church that they know, because most of them still retained their faith, remarkably enough. That's really all they're looking for.

Unfortunately the minute certain members of the Church hear this, they jump on that, because it's a financial organization, and they think, "Well, that's okay. We'll give you that. Just don't go looking for any money from us." Already they came up with a package of 180 million euros for children who were the victims of abuse by the clergy in Ireland, and it excludes Magdalene. The reason it excludes the Magdalene women is because they supposedly went there voluntarily. So because they didn't go through the court system, they're now on a technicality able to cut the women out of that particular financial package.

The only reason there's been no outcry about it is the women aren't particularly interested in the financial package. I think when you've been through an experience like that, and your life's been screwed up as a result of it, you realize money isn't going to solve it. Money's not going to give back their relationships that didn't work because you couldn't relate to someone because you didn't understand your own sexuality. No money's going to cure that. It's not going to make up for the child you've not seen in thirty-five or forty years. I think those women are deep enough to realize that money is of no great consequence. And unfortunately…the Church, they sometimes take advantage of that.

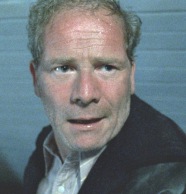

Peter Mullan in Session 9. |

Question: What finally shut down the Magdalene Laundries?

Mullan: Economics. They ceased to be economically viable around the late Seventies or early 1980s, coinciding with the domestic washing machine and the very slow beginnings of the "Celtic Tiger" economy. Ireland's GNP has had the highest growth in the last seven to ten years of any country in the developed world. It's running at something like three and half, four percent per annum, and has been for about the last ten years. No other country can claim that. In fact, in the entire nineteenth century, I don't think there's a single country that could have claimed that over a ten year period. So Ireland of the great economic miracles of modern Europe.

With that factor, the capitalists moved in. There was money to be made. So on the one hand, you've got the domestic washing machine [which] ceases to make this very labor-intensive laundry business particularly profitable. Simultaneous to that, running parallel, is a group of industrialists—modern hi-tech industrialists—they don't want no women not getting dressed up, because then there's no way to sell the lingerie, the shoes, the clothing. They want young women to be reading young magazines, thus they consume the magazines. They want them on mobile telephones; they want them using nail varnish; they want them going out to clubs and drinking their beer. You know, it's a consumer society now. That's one of the main [reasons] the Church has virtually nothing like the say that it used to have.

At the time of the Magdalenes, they provided a very large and cheap workforce. I honestly believe there's a thesis that could almost argue that the modern Celtic Tiger economy is based on child slave labor. Because when you add together the Magdalene Asylums and the industrial schools, it's an enormous unpaid workforce of kids—well, young adults, age sixteen to whatever. If one could get that information together, I really think you actually might have a case. I'm not saying it is built upon that, but I reckon you would have a case to argue.

Question: You based several of the girls on real people. Where did your characters of the nuns come from?

Mullan: I worked for them. I worked for Sister Bridget for three months when I was seventeen.

Question: And she said something to you that you never forgot, correct?

Mullan: She said many things that I never forgot. When we first met her, she said prayers for these two Scots lads who had come down to work with single homeless schizophrenic women. As we looked up, she had a full-size portrait of Benito Mussolini on her wall. Card-carrying fascista.

|

|

Question: We first think of you as an actor. You've always wanted to be a filmmaker, though.

Mullan: Aye.

Question: Can you just tell us how you got into acting, and how it balanced with filmmaking?

Mullan: The acting, I got into—I did what we call "pantomime"—a Christmas show—when I was sixteen. There was lots of very pretty girls in the show, and I was kind of lead comic, so I found out very early on, lead comic gets the girl, so that was cool. When I went to university, I studied economic and social history, and drama. My main ambition was to make films; it was never to be an actor. At that time there weren't many opportunities for working class Scot actors. It was kind of an English thing, and it required a certain mannered cerebral acting style that I couldn't relate to.

In my final year of university, I had a massive nervous breakdown. About a year and a half, two years later, I did a student production when I was teaching at the university, and in this particular play, the character had a massive nervous breakdown. That was a big moment in my life, because I got to play [the part as] someone who had experienced it just two years previous, and instead of condemnation or people feeling sorry for me, they gave me a round of applause, a pat on the head, and a nice review.

Question: Why did you have a nervous breakdown?

Mullan: [shrugs] Good question. Eh…I found myself working, I was working about sixteen, seventeen hours a day for about five weeks to my final exams. I'd won a lot of class prizes at university, and I decided in that state of stress, that I was actually the thickest person I knew. I decided I was dumb as fuck. Once you do that in a state of stress, it's not a particularly good place to be. So I went on a kind of self-destructive mode. Very Catholic thing. [laughter] I decided that I was undeserving of what I had achieved, and I decided to punish myself accordingly.

But, to realize that on a stage you could get that out of your system is what taught me what I still now know, which is acting is the greatest job on earth. You can do the most boring job—I worked in checkouts for two years as a student, and you bag the groceries or whatever you guys call them [in America], and I could dream a life away. The women that I worked with, that was them for life, whereas I could dream a life away, and one day maybe even get to live out those particular fantasies. In acting you can tap into the darkest, darkest moments of your life to the lightest moments in your life, and people will watch it and appreciate it and even engage with you because of that. That's the greatest job on earth.

Question: But now there are also the satisfactions of filmmaking and writing.

Mullan: Filmmaking is something I have to do. It's not something I particularly want to do. Howard Barker said that it's not that he wants to write plays, he has to write plays, and I kind of feel that about directing. Acting is a lot more fun. Jesus, you wander around, you're spoiled rotten, and at the day, you go, "See you in the pub." I mean, that's a nice job. And I work in low budget films, so it's not like we get particularly well paid for it. But man, we can just have a ball.

Directing's twenty-four-seven, nobody off your fucking case. Everybody wants a piece of you. You're dizzy by Week Two. You're panic-stricken by Week Three. You're starting to relax by Week Four. You're just about having the breakdown in Week Five, and then you finish the film by Week Six. It's very masochistic. It's very wearisome, and you know that it doesn't finish there. That's the worst thing. You know that a year down the line, quite rightly, you're going to face you guys [indicates reporters], and an audience, and your family, and the Pope, and everybody quite rightly has an opinion. And they ain't all going to like your movie. So it's much harder than acting. Writing's good fun. On a good day—as you guys know—writing's great. On a bad day, it's very suicidal. On a good day, you feel you've achieved something, and maybe it might be worth something.

Question: As far as the acting goes, that scene in Magdalene Sisters where Eileen Walsh [who plays Crispina] says, "You're not a man of God," twenty-seven times—

Nora-Jane Noone and Eileen Walsh in The Magdalene Sisters. |

Mullan: Is that how many times she says it?

Question: Yeah.

Mullan: Cool.

Question: Was it scripted that way?

Mullan: In the script, I said that she said, "You're not a man of God" like a mantra, and she doesn't stop. When Eileen came to play it [and] when we first shot it, I think Eileen said it twice, and that was it. So I said, "Cut," and Eileen and I spoke about it. It was about the only good direction I think I gave Eileen—I didn't really have to give Eileen any direction. The only thing I said to her was, "It's like the words 'You're not a man of God' are stapled to the side of mortar fire, and the mortar is inside your gut, and it's been there for seventeen years." So we had the guy playing the priest run off camera, and I told her, "However far he gets, it's another piece of mortar fire. It's like your gut contracting." And instead of it coming out shaped like mortar, it came out as, "You're not a man of God." If you watch her, you actually see her head go up. She's literally firing this anger at this guy. And then, in the second take after that, I asked him to move around, so that she fired it wherever he went.

Language can get rolled up in a kind of emotional shell, and then just explode at someone like, as I say, a muscular contraction. And the funding morons, when they watched the film—the screening—we had one arsehole saying, "Oh, there's too many. Oh, there's far too many." Then you got another wanker saying, "There's not enough of them. I'd like to see more. I think you cut some of them out." And it's like, "Oh, fuck off. Leave it to me. Guys, I will decide how many there are." Jesus, everybody's going to have a different opinion about it; everybody's going to have a different idea. Is it too long? Is it too short? As a director, all you can do is go by your instincts and go, "No. Keep going." Because this is something that has built up in this young woman.

It's like when you cut a film, oftentimes there's no rationale behind cutting there, or there. There was a brilliant note on the day before we finished cutting the film. We had another screening of it, and there's a girl sneaked into the screening that worked in that art theater. She said, "Can I sit and watch it?" "Absolutely." So she sat and watched the film. And she said, "Oh, amazing, loved, it, blah, blah, blah." I said, "Have you any nuts-and-bolts kind of notes, because we finish tomorrow. We picture-lock tomorrow." And she went, "No, it really blew me away, blah blah blah." Then she went, "Well, there's one. There's just one thing. I don't think you need Crispina being dragged down the corridor. I think you could cut from upstairs to the nun coming back in."

So we went back and I said to my editor, "Let's see what happens." We cut it from upstairs with her screaming and the girls crying, to the nun coming in. Perfect. It was absolutely perfect. It was a beautiful cut. It was getting kinda late, and I wanted to go home, and I said to my editor, "It works. It definitely works." And I said, "But there's something worrying me here. We have to watch this film now from the fucking beginning, right to the end." We'd watched [it] a zillion times. We'd got this film as tight as we could get it. The scene in the corridor was nine second long, and [we thought] there was no way that we could screw up the film by taking out that nine seconds. Because Alison—that was the girl's name—she was absolutely correct.

We watched the film, and the most unbelievable fucking thing happened. That scene worked a dream. It was perfect. You go from upstairs to the nun, blah blah. Crispina has disappeared. [But] the end of the film didn't work. The last scene with Crispina didn't work. It was superfluous. And I'm so glad I watched that film again from start to finish, because I loved that last scene. I loved what she was doing. And suddenly you thought, "That has to go." That happens in cutting a film all the time. You take one thing out and you realize you don't need that [other] thing, and you can lose some of your favorite scenes. But suddenly the whole film takes a different dynamic. What was fascinating, for nine seconds, we screwed up the ending.

I know for a fact that her cut, for that moment, was much better than the cut we've got. But I also know that nine seconds gave Crispina an exit, an exit along a recognizable area. Margaret leaves there. Bernadette, and Patricia, they all exit via that corridor. If we didn't have [Crispina] coming down the corridor, she's not had an exit. She doesn't merit the final scene. So it's fascinating how much you can learn simply by taking on the notes of someone else, and seeing what works, and what doesn't. And I have no idea where that came from, but never mind. I just rambled on there. I don't think I answered a single question. Anyway.

Question: At Sundance there was a similar film called Song for a Raggy Boy that looks at the experiences of boys in a reformatory.

Mullan: I know, I've not seen it. This is the Aidan Quinn film?

Question: Yes. How much is this a subject that needs to be talked about right now, specifically about what happened in Ireland? Do you think there will be more films about this subject matter?

Mullan: I do. I do. And people quite rightly might well get sick of it. And the Church will say, "Oh my God, it's a new genre. Blah-dy blah-dy blah." The bottom line is, you'll know instinctively if some asshole is exploiting this. The audiences will know. They'll know immediately, "This person is glad that this happened, because they got to make this film." And they'll know instinctively the ones who felt that the film was important for the people that suffered what they suffered, and to prevent it ever happening again. There is no doubt that some people will exploit it. Absolutely, if they haven't already. It wouldn't surprise me in the slightest. Unfortunately there are filmmakers out there who, the more miserable a life that someone leads, the happier they are because they get to make a film about it, and maybe make money out of it. I think for those of more genuine intent, if this thing keeps happening, God forbid, then you have to keep looking at it. If it doesn't happen, then there's nothing to look at. To be honest, the ball is firmly in the court of the Church. For them to turn around and say, "Why are you guys making all these films?" It's like, "Well fucking stop having your priests abusing people!" Then we wouldn't have anything to make the film about.

Question: It's also that you can finally talk about it now that all these stories have come out, whereas you couldn't talk about it before.

Mullan: Absolutely. In Ireland, the censor said to us that he gave it the certificate that he gave it, which made it open to all kids over the age of twelve—he said that five years ago he couldn't have given it any certificate, because the Catholic Church wouldn't have allowed it. It simply wouldn't have been passed. So we would have been condemned solely to the art houses. We wouldn't have been allowed to actually show the film in the multiplexes and the like. So the Catholic Church has been smart to realize, "Back off, guys, because this issue is just way to important for you guys to be slapping on some surreal certificates." Although I do believe it's an R-17 or whatever over here.

Question: You mean NC-17? No, it's an R.

Mullan: An R? Is that worse than an NC-17?

Question: No, an NC-17 means you can't show it hardly at all.

Mullan: Oh, so an R is below that. But does that mean fourteen, fifteen-year olds can see the film?

Question: With an adult. If they're accompanied by an adult.

Mullan: Oh, that's not so bad.

Question: Can you tell us quickly, before we go, about Young Adam and reuniting with Ewan McGregor? You're working with him again?

Mullan: [tongue in cheek] Young Adam is Ewan McGregor at his most spectacularly handsome. Ridiculously handsome. He gets something like twenty-eight sex scenes, and I get to play this impotent cuckolded husband, because it's my wife that he has about ten of those sex scenes with. So, it's a highly embarrassing part. McGregor in the film is astonishing. He would make Montgomery Cliff blush. Honestly, he is spectacularly handsome, and movie stardom suits him. Some guys it doesn't suit. They don't carry it well. Ewan's getting to be pretty damn unique. Like Connery. Movie stardom suited Connery. In his early films, Connery's still trying to be an actor. When Connery realized who and what he was, it all came together, and he became that phenomenally handsome, sexy kind of guy, a man's man, and also a guy that women would like to be with. Ewan's going in that direction. He's also—and I'm not just saying this—he's also a very very lovely guy. He's a great guy to work with. He's actually a real human being. He's not some idiotic movie star with an IQ of a daffodil. He's complete now, and he gets all the good sex scenes.

[Continue to the review of The Magdalene Sisters]

Feature and Interview ©

August 2003 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images of The Magdalene Sisters © 2003 Miramax Film Corp. All Rights

Reserved.

Image of The Claim © 2000 United Artists Pictures, Inc. All Rights

Reserved.

Image of Session 9 © 2001 USA Films, LLC. All Rights Reserved.