|

|

||

|

France,

1999. Unrated. 90 minutes.

Cast:

Denis Lavant, Michel Subor, Grégoire Colin |

|

| Grade: B | Review by Jeff Vorndam |

![]() ou

will likely not see a more beautiful film this year than Beau Travail.

It's also likely you will not see a more enigmatic and confounding film.

Claire Denis' latest is hypnotic. The film's rigorous rhythm will spellbind

the more suggestible movie-goers and put the more resistant to sleep.

ou

will likely not see a more beautiful film this year than Beau Travail.

It's also likely you will not see a more enigmatic and confounding film.

Claire Denis' latest is hypnotic. The film's rigorous rhythm will spellbind

the more suggestible movie-goers and put the more resistant to sleep.

I found the film both patience-trying and alluring. It's

a curious feeling. Even though I remember shifting in my seat several

times, I can't get the film out of my head. Its images of azure waters

and salt-white sands flood my mind and the pitted, seething face of Denis

Lavant sears my memory. Beau Travail isn't for you if you demand

your images wed to a strong narrative or well-rounded characters. Its

story is only loosely derived from Herman Melville's Billy Budd, Sailor,

and its characters are sculptures to be observed from a distance. Nevertheless,

the film's intractable quality imparts a state of foreignness and alienation

that lingers long afterward.

Set in Djibouti in the present day, Beau Travail regards with a distant eye the repetitive and pointless tasks of French Foreign Legionnaires stationed there. The Legion is somewhat of an anachronism these days, an outpost for hardened antisocial types. Galoup (Denis Lavant) is their taskmaster, assiduously prepping the men with drills and exercises under the cryptic eye of the Commander, Bruno Forestier (Michel Subor, who played a character of the same name in Jean-Luc Godard's Le Petit Soldat). Into this grueling routine arrives a newcomer, the fresh-faced and handsome Gilles Sentain (Grégoire Colin, recently seen in The Dreamlife of Angels). Sentain inspires an irrational jealousy in Galoup after Sentain saves the life of a fellow Legionnaire. It's not clear whether Galoup's mounting obsession and hatred of Sentain is due to a denied homosexual attraction or if Galoup believes Sentain is diverting favor from the Commander that he used to bask in himself. No matter, the story of the movie is the march toward the inevitable moment when Galoup reaches his breaking point.

Cinematographer Agnes Godard performs brilliant work here. The men are photographed rapturously. Their sinuous bodies reflect the desert heat and their motions across the frame achieve the symmetry of the spaceship waltz in 2001. Her woman's eye is crucial to this film because it is Denis and Godard's status as outsiders mesmerized by male ritual that imbues the film with an extra shading beyond what would typically be read as homoeroticism. Because the events depicted are monotonous, and dialogue is kept to a minimum, my attention was riveted to the photography. The desert puts the men into relief; they stand out crisply against their austere surroundings. Their actions–crawling under barbed wire, digging ditches, vaulting over wooden beams–emphasize a struggle to impose order on an untamed land, and to master themselves as well, creating machines of clockwork precision. The gravitational pull of Galoup and Sentain's conflict discharges them from their imposed discipline. They are being released from a rigid order, but only by succumbing to a trap. In the climactic scene, the two men circle each other in a decreasing radius, while Benjamin Britten's Billy Budd opera soars in the background. These are men trapped by their definitions, and the only recourse each has is to eliminate the other. If Denis were prone to a Western cliche she'd have Galoup declare, "This Legion ain't big enough for the two of us."

In the end, perhaps even Galoup isn't big enough for himself.

In a bizarre coda at a European discotheque, Galoup performs a spastic

dance that looks like a man who wants to escape from his own kin. It's

a poetic finale to a film that never pinpoints an idea but is content

to allow scenes to float by slowly.  I

was at first baffled by the ending. Its presentation made me chuckle,

even though it is essentially sad and desperate. After ninety minutes

of ambiguity, it feels like a non sequitur. But it's also a rage against

the machine, a fitting destruction of the code embodied by taciturn men

of action like Clint Eastwood and, more recently, Russell Crowe. Denis

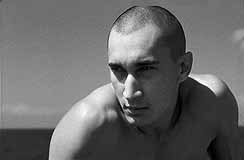

Lavant's performance is excellent. He transmits the slow-burn in his eyes,

and his ragged features imply that he's been around the block a few times.

Less successful is Gregoire Colin, who doesn't have the necessary personality

to attain the respect and admiration of his fellow soldiers. He's more

of an object, his presence no more special than that of any other member

of the squadron.

I

was at first baffled by the ending. Its presentation made me chuckle,

even though it is essentially sad and desperate. After ninety minutes

of ambiguity, it feels like a non sequitur. But it's also a rage against

the machine, a fitting destruction of the code embodied by taciturn men

of action like Clint Eastwood and, more recently, Russell Crowe. Denis

Lavant's performance is excellent. He transmits the slow-burn in his eyes,

and his ragged features imply that he's been around the block a few times.

Less successful is Gregoire Colin, who doesn't have the necessary personality

to attain the respect and admiration of his fellow soldiers. He's more

of an object, his presence no more special than that of any other member

of the squadron.

Translated from the French, Beau Travail means "good work," and Denis' film is indeed that. It wasn't the most enjoyable film I've seen recently, and some stretches were frankly rather boring. Once the movie was over though, I liked it a lot more. Memory has a way of selecting the finer moments of an experience and replaying them again and again. Right now I picture the fantastic dance of soldiers in the desert, bear-hugging, their skin slapping against each other. I don't know what it means, but it resonates all the same.

Review

© May 2000 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images © 1999

Pyramid Films. All Rights Reserved.

|

|