|

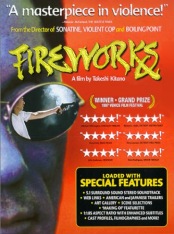

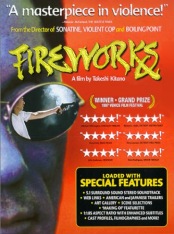

Fireworks

aka Hana-bi

|

| |

|

Japanese language. Japan, 1997. Rated R.

103 minutes.

Cast:

Takeshi Kitano (as "Beat" Takeshi), Kayoko Kishimoto, Ren Osugi, Susumu

Terajima, Tetsu Watanabe

Writer: Takeshi Kitano

Original music: Jô Hisaishi

Cinematography: Hideo Yamamoto

Producer: Masayuki Mori, Tasushi Tsuge, Takio Yoshida

Director: Takeshi Kitano

LINKS

|

f

we accept that Japanese art favors minimalism and understatement, then Fireworks

must surely be one of the most Japanese films ever. Writer/director/star Takeshi

Kitano (Sonatine) makes movies that marry

poetic beauty with vicious, unglamorous violence. For this reason, he has been

likened to Martin Scorsese, but their cinematic voices are totally different.

Scorsese's films are active, energetic epics filled with aggressive tension,

so much so that he sometimes desensitizes his audience to the violence. Kitano

makes static, understated movies about existences wasted, and rediscovering

the joy of being, for a brief time, alive. Rather than a constant presence (overt

or implied), violence comes in sudden bursts, as a shocking interruption.

f

we accept that Japanese art favors minimalism and understatement, then Fireworks

must surely be one of the most Japanese films ever. Writer/director/star Takeshi

Kitano (Sonatine) makes movies that marry

poetic beauty with vicious, unglamorous violence. For this reason, he has been

likened to Martin Scorsese, but their cinematic voices are totally different.

Scorsese's films are active, energetic epics filled with aggressive tension,

so much so that he sometimes desensitizes his audience to the violence. Kitano

makes static, understated movies about existences wasted, and rediscovering

the joy of being, for a brief time, alive. Rather than a constant presence (overt

or implied), violence comes in sudden bursts, as a shocking interruption.

Fireworks concerns Nishi (Kitano), an oft-decorated detective who leaves

his partner Horibe (Ren Osugi) alone on a stakeout to visit his terminally ill

wife (Kayoko Kishimoto), during which time Horibe is shot and paralyzed. Nishi's

subsequent vendetta inadvertently results in the killing of another detective,

Tanaka (Makoto Ashikawa), and the wounding of a third, Nakamura (Susumu Terajima).

Wracked by guilt and disgusted by the police force's failure to nurture its

own, Nishi quits to provide for his colleagues and ease his wife's last days—by

any means necessary.

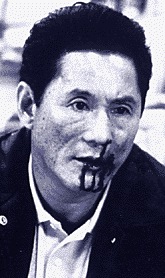

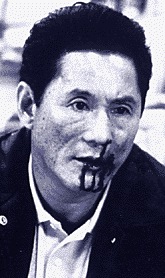

A bloodied Takeshi Kitano in Fireworks |

The second half of the film takes an odd Kitano turn, as Nishi and his wife

rediscover the simple delights of relaxing at the beach or fooling around with

a deck of cards. They play. They set off simple fireworks in a field, whose

sudden bursts in the tranquil countryside are like Nishi himself, calm, easily

contented, yet explosively violent when set off. Yet even in quiet moments,

an aching melancholy lingers between Nishi and his wife, attributable both to

her terminal illness and to the recent death of their young child. Death for

Nishi, in the form of the yakuza loan sharks hunting him, is also never

far away.

As he has in other movies, Kitano the director puts Kitano the actor at the

center of Fireworks, where he performs with an disconcerting impassivity.

His favorite reaction shot is an expressionless closeup of himself. He never

seems to say anything. Rather, other people say things to him. He waits,

he considers, and when the moment is right, he acts, with forceful, bloody determination.

Hideo Yamamoto's camera is equally impassive. It rarely pans and almost never

zooms. Often Yamamoto and Kitano establish a shot for a second before the action

moves into it, and allow the shot to continue running for a moment after the

action has left, much as Kurosawa does. This technique serves to emphasize the

permanence of the surroundings and the impermanence of the people who pass through

them, suggesting life is short. Find ways to enjoy it, Kitano is saying, even

if the enjoyment cannot last.

This is where Kitano is a social critic. In Japan, the conformist pressure

to dedicate your life to an employer, and to always do your duty, is much stronger

than it is here. Nishi and his colleagues spill their blood for the police and

the public good, and what do they get in return? Whatever disability payments

Horibe might be receiving are insufficient even to buy painting supplies, not

that he has any idea how to enjoy his new hobby, which he regards only as a

way of passing the time. Work is all Horibe has ever known. Nakamura echoes

this sentiment when he observes a girl running with a kite on a beach, and remarks,

"I could never live like that." Evidently pensions and medical benefits also

leave a lot to be desired, because Tanaka's widow (Yûko Daike) is reduced to

working at a fast food counter, and Nishi has borrowed millions of yen to pay

for his wife's treatments.

Kitano never expresses any of his opinions straightforwardly—or the plot,

for that matter. Like his impassive protagonist, Kitano says little, and he

feeds us the story piecemeal, sometimes via flashbacks spliced into the film

with no commentary. It takes a good half hour to forty-five minutes before even

the basic premise is discernible. The film is like the dots on Horibe's pointillist

painting—Kitano fills in a bit here and a bit there, in no particular order

but with painstaking attention to detail, and the big picture gradually emerges.

Horibe's artwork in the movie is actually Kitano's own work, much of it serenely

whimsical, from the primitive paintings at the hospital to Horibe's figures

of animals with flower buds in the place of their heads or eyes. Kitano often

juxtaposes a thing—raindrops, cherry blossoms, and, of course, fireworks—with

a painting of the thing. Life and art are the same, indistinguishable, like

the shot of a blue Mount Fuji set against a blue sky, looking exactly like a

two-dimensional Japanese print. The most arresting artwork in the film, though,

is a large painting of a snowy landscape at night that, similar to a pointillist

work, is actually composed of a multitude of tiny kanji

(Japanese) characters that spell out each element of the painting (e.g.,

the snow is made up of tiny characters that mean "snow"). In the middle, splashed

in red, a much larger character violently mars the painting's tranquillity.

If you haven't yet seen the film, it is best that you find out what the character

represents for yourself. The tone of the painting, however, corresponds to the

tone of the film. For Kitano, human life is like one of Nishi's fireworks in

the countryside—it begins as a spark, then explodes as a momentary, ferociously

intense flash in an otherwise serene world.

Review

© October 2003 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.