| Gladiator |

| |

|

USA, 2000. Rated R. 150 minutes.

Cast: Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix,

Connie Nielsen, Richard Harris, Oliver Reed, Derek Jacobi, Djimon Hounsou,

Spencer Treat Clark, Ralph Moeller, Tomas Arana, Chris Kell, David Hemmings

Writers: David H. Franzoni, John Logan,

William Nicholson

Music: Hans Zimmer, Lisa Gerrard,

Klaus Badelt

Cinematographer: John Mathieson

Producers:

David H. Franzoni, Steven Spielberg, Douglas Wick

Director:

Ridley Scott

LINKS

|

here's something

admirably brave about Ridley Scott's (Alien,

Blade Runner) attempt to reconfigure

the Cecil B. DeMille ancient epic genre in a way that will retain the grandiosity

and melodrama without offending modern sensibilities, which lean decidedly toward

a preference for realism over gaudy excess. No easy task. With Gladiator,

Scott manages to succeed and fail, almost in equal measure. The

film is beautifully rendered visually, employing a plethora of impressive effects

in service to both realism and surrealism. The performances–major and minor–are

subtle, heartfelt, and straightforward. The story pits recognizable good against

recognizable evil in the form of credible characters, and has its heart in the

right place. The direction is intermittently awesome. All in all, it's a very

well-made film and an entirely honorable effort. So why was I left somewhat

cold?

here's something

admirably brave about Ridley Scott's (Alien,

Blade Runner) attempt to reconfigure

the Cecil B. DeMille ancient epic genre in a way that will retain the grandiosity

and melodrama without offending modern sensibilities, which lean decidedly toward

a preference for realism over gaudy excess. No easy task. With Gladiator,

Scott manages to succeed and fail, almost in equal measure. The

film is beautifully rendered visually, employing a plethora of impressive effects

in service to both realism and surrealism. The performances–major and minor–are

subtle, heartfelt, and straightforward. The story pits recognizable good against

recognizable evil in the form of credible characters, and has its heart in the

right place. The direction is intermittently awesome. All in all, it's a very

well-made film and an entirely honorable effort. So why was I left somewhat

cold?

Gladiator tells the story of Maximus (Russell Crowe), a Roman general

whose leadership and dedication have helped expand the Roman Empire to Germany,

where we meet him as he prepares to battle the barbarians. Separated from his

beloved wife and son for more than three years, Maximus longs to resign his

commission and return home. The arrival of Emperor Marcus Aurelius (Richard

Harris) at the battlefield dashes this hope a bit. He has other plans for his

loyal warrior, which he reveals in a clandestine tête-à-tête.

It seems that the Emperor has grown weary of the direction that the Roman Empire

has taken, finding little joy or value in the vast expansion that relentless

conquest has yielded. In addition, he is clearly nearing the end of his life,

and has come to believe that the greatness of Rome cannot prevail without a

return to the rule of the people via the political mechanisms of the Republic.

He is an emperor who believes that there should no longer be an emperor. His

conviction is further strengthened by the fact that his amoral and immature

son, Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix) is next in line for the throne. Marcus Aurelius

tells Maximus that–upon their return to Rome–he will appoint him Lord Protector

and then step down... his aim being that Maximus (who is pure of heart

and not the least bit ambitious) will safeguard the transition back to representative

government. When Commodus is informed of this plan, he murders his father and

orders the execution of Maximus, who escapes this fate and–through a complex

set of circumstances–ends up being appropriated as a gladiator. The remainder

of the film charts his rise as a star in the arena, his efforts to seek revenge

on Commodus, and his hope of somehow honoring the wishes of Marcus Aurelius

regarding the political fate of Rome.

It's a fairly standard epic tale, and a decent enough one to tell, but Scott

and his screenwriters focus too much on plot advancement and too little on thematic

or character development. Russell Crowe brings his awesome physicality and a

healthy measure of intensity and dignity to Maximus, but the script gives him

little else to work with in terms of building a character. He is–essentially–a

good man unfairly victimized by a bad man. We hope he prevails, of course, but

we never penetrate his surface to a degree that makes us truly yearn

for his ultimate victory. Part of the problem is that the story is too insular

with regard to his personal quest, and that his personal quest is too personal.

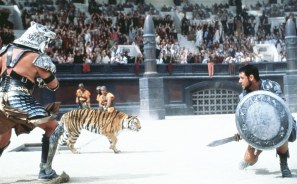

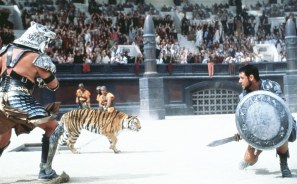

Though we see Maximus as a gladiator, there is no attempt to portray what that

means beyond the obvious.  Unlike

Spartacus, which concerned itself with the many ways that such slavery

was both deadly and–even in survival–a fate worse than death, Gladiator

contents itself with mourning the unfairness of this one man's fall into such

lowly and cruel circumstances. Maximus is no crusader against this disgusting

"sport", he's just an angry and righteous man who hopes to survive long enough

to find justice. There are flickers of thematic resonance, but they're never

pursued beyond minimal suggestion. The "battles" that are waged between the

gladiators are staged more like mini-wars than mano-a-mano struggles, which–particularly

when Maximus rises to the occasion and asserts himself as a leader for his "team"–suggests

that his job hasn't really changed much, except that now he's leading battles

merely for the immediate pleasure and amusement of the citizens he used to serve

in the field. The moment resonates a bit, because Marcus Aurelius had earlier

lamented that his popularity with Roman citizens was largely earned through

the reflected glory they felt from his conquests. Scott has no interest in examining

the nature of this blood-lust, however. It is shown, but not in a revelatory

way. As for the issues addressed in the political goals of Maximus (restoring

the Republic), they never rise to the level of passionate importance for the

audience, because Maximus is motivated more by his loyalty to the dreams of

his dead Emperor than by any personal passion he feels for the issue itself.

If it weren't for the fact that Commodus is so obviously ill-suited to ruling,

we probably wouldn't care at all about restoring the Republic.

Unlike

Spartacus, which concerned itself with the many ways that such slavery

was both deadly and–even in survival–a fate worse than death, Gladiator

contents itself with mourning the unfairness of this one man's fall into such

lowly and cruel circumstances. Maximus is no crusader against this disgusting

"sport", he's just an angry and righteous man who hopes to survive long enough

to find justice. There are flickers of thematic resonance, but they're never

pursued beyond minimal suggestion. The "battles" that are waged between the

gladiators are staged more like mini-wars than mano-a-mano struggles, which–particularly

when Maximus rises to the occasion and asserts himself as a leader for his "team"–suggests

that his job hasn't really changed much, except that now he's leading battles

merely for the immediate pleasure and amusement of the citizens he used to serve

in the field. The moment resonates a bit, because Marcus Aurelius had earlier

lamented that his popularity with Roman citizens was largely earned through

the reflected glory they felt from his conquests. Scott has no interest in examining

the nature of this blood-lust, however. It is shown, but not in a revelatory

way. As for the issues addressed in the political goals of Maximus (restoring

the Republic), they never rise to the level of passionate importance for the

audience, because Maximus is motivated more by his loyalty to the dreams of

his dead Emperor than by any personal passion he feels for the issue itself.

If it weren't for the fact that Commodus is so obviously ill-suited to ruling,

we probably wouldn't care at all about restoring the Republic.

There are other problems that thwart substantial emotional engagement with

the story, and they largely come from undeveloped details. When Maximus lands

back in Rome, he is reacquainted with Lucilla (Connie Nielsen). She is Commodus'

sister, and apparently an old flame from Maximus' past. Their shared history

is alluded to but never explained, which would be fine if certain moments didn't

seem to deliberately raise questions about the nature of their past, only to

leave those questions dangling and unanswered. It makes no sense for Scott to

choose such an intimate, insular story to tell if he's not going to flesh it

out with the sorts of details that will tell us more about who these people

are and why we should invest our emotions in their actions and their fates.

Nielsen gives a lovely performance, but her character is the most sketchy of

the three who dominate the bulk of the film. She handles every scene with a

gracefully subtle emotionalism, but–beyond her immediate dilemma of straddling

the space between her loyalties and fears–we never come to know much about who

she is, except in relation to the two men she's dealing with. The one character

who escapes this superficial treatment is Commodus, and thus, his scenes are

almost always the most engaging, well-written, and emotionally interesting.

Joaquin Phoenix is marvelous in the role, bringing an edgy despondence to a

character who could easily have been little more than a comic-relief wuss. His

petulance is more juvenile than prissy, and his displays of emotion are–at times–genuinely

touching, even when they're menacing. Wracked with unquenchable envy and lifelong

bitterness regarding his father's more substantial love for Maximus, Commodus

is a pitiable overgrown child wearing an emperor's crown and wielding unlimited

power. We can't stand the guy, but he's a lot more fun to watch than anybody

else in the movie. In that sense, Commodus (as a character) and Phoenix (as

an actor) are the story's saving grace.

AboutFilm.Com

The Big Picture

|

| Alison |

B+

|

| Carlo |

A

|

| Dana |

B

|

| Jen |

A-

|

| Jeff |

B+

|

| Kris |

C

|

| ratings explained |

Regardless of the inherent limitations of the storytelling choices, the performances

in Gladiator are unwaveringly excellent. Scene by scene, the events always

remain watchable, because this cast is so emminently watchable. (Though Hans

Zimmer's overblown, occasionally grating score sometimes undermines their efforts,

particularly in the first third of the film.) The trio of veteran British actors

who represent the Old Guard of Roman society bring charisma and gravity

to their roles. Richard Harris' world-weary regality is perfect for Marcus Aurelius,

who is the true spiritual center of the film's thematic content. It's sad to

see this character exit so soon, both for the emperor's presence in the story

and for Harris' presence on the screen. Oliver Reed (sadly, in his final role)

is a different kind of world-weary as Proximo, the trainer/caretaker of the

gladiators. A former star of the arena himself, he's a bit of an interesting

contradiction, playing a crucial role in a repugnant system without seeming

to find it unbearably repugnant. The games are his livelihood and the source

of his former glory, so it makes sense that he'd deny himself access to any

deeper feelings about what he's doing. Still, there's a sadness to him that

mixes nicely with his practical side, and the ways that he chooses to mentor

and assist Maximus ultimately belie his apparent lack of conscience. Of particular

delight to me was the presence of the magnificent Derek Jacobi as Gracchus,

a Roman senator whose street smarts and integrity give hope to the idealized

notion of eventual Republican rule. Jacobi conveys intelligence and character

so instinctively and effortlessly that he brightens every moment in which he

appears. Too bad they are so few. And too bad he is not cast more often in films.

That such a resourceful and gifted actor is routinely ignored by the industry

truly baffles me. Kudos to Scott for seeing what others have missed.

What Gladiator lacks in narrative resonance is almost successfully offset

by what it provides visually. The look of the film is often breathtakingly beautiful,

ranging from awesome (if not entirely accurate) recreations of Roman structures

and cityscapes to evocatively surreal sequences that approximate a dream state.

At one point, the spiritually-grounded, deeply philosophical gladiator played

by Djimon Hounsou (underused, but terrific!) looks up at the Colosseum in wonder,

remarking that he can't quite believe what man is capable of creating. It's

a great moment, and it cuts two ways in the film, because it's equally unbelievable

that the same creature who conceives such magnificence could also conceive the

monstrous purpose for which that structure is used. The moment resonates on

a third level, as well, because I instantly felt the same awe at the state of

visual effects in movies. It's amazing to gape at these virtual restorations

and realize what can now be achieved so seamlessly with a complex set of tricks.

Wisely,

Scott saves the best visuals for the last third of the film, helping to retain

our interest in spite of the running time and the somewhat skimpy level of engaging

subtext.

Wisely,

Scott saves the best visuals for the last third of the film, helping to retain

our interest in spite of the running time and the somewhat skimpy level of engaging

subtext.

Oddly, the aspect of the film where Scott stumbles most grievously is in his

staging of the action sequences. The opening battle scene is fantastic for its

look: a melancholy blue-gray hue informs everything until the carnage ceases,

at which point, the bloody aftermath is presented in red light, which emanates

from the burning forest that surrounds them. Lovely! Unfortunately, the battle

itself is shot and edited in a manner that suggests mayhem but renders it largely

incomprehensible. It's impossible to react emotionally to any of it, either

as horrifying carnage or lamentable human exploits, because you can't tell what

the hell is happening in any given moment. By comparison, Mel Gibson's achievements

with Braveheart's exceptional battle sequences stand as even more impressive

for their raw power and sense of realism. Scott's direction keeps us removed

from the battle, despite the placement of the camera within the battle. A huge

mistake. The bulk of the gladiator battle sequences are no more comprehensible.

You understand the basic dynamics of what's happening. You understand the results

of the action. But the action itself is a jumble of quick cuts and suggested

carnage that is mostly impenetrable beyond general notions of who's doing what

and which side is prevailing. Again, a huge mistake. Instead of being on the

edge of your seat, you'll more likely be furrowing your brow and trying to make

sense of what you're seeing. The net result robs the audience of genuine involvement

on a moment-by-moment basis. If you're looking for action that can be rightly

deemed "rousing," Gladiator is not the place to find it. Perhaps this

was a deliberate choice that reflects Scott's desire to avert undue pleasure

in morally reprehensible carnage? Doubtful. But if that's so, it's still a mistake,

even if an arguably admirable one, because he doesn't replace potential thrills

with anything else to hang onto. The scenes are no more elegiac than they are

rousing.

By the end, I felt respect and admiration for most of the elements of the filmmaking

and performances, but little satisfaction in the realm of emotional catharsis.

I never cheered, and I never cried. Perhaps that's too much to ask, but considering

the obvious sincerity of the production, I don't think so. Gladiator

is full of attention to detail in many ways, but rarely takes the opportunity

to provide the sorts of small moments that bring characters (even iconic ones)

and ideals to full-blooded life. And though there is plenty of visual spectacle

to fall back on, the lack of emotional engagement makes watching this film an

interesting–but curiously detached–experience. I hate to think that the failures

of Gladiator might boil down to the fact that it is simply too dignified

for its own good, but a case could be made for that point. If it wasn't going

to delve more deeply into theme or character anyway, Gladiator might

arguably have benefited from some of the gaudy excess of those DeMille epics

after all.

Review

© April 2000 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images TM & © 1999 DreamWorks LLC and Universal Studios.

Unlike

Spartacus, which concerned itself with the many ways that such slavery

was both deadly and–even in survival–a fate worse than death, Gladiator

contents itself with mourning the unfairness of this one man's fall into such

lowly and cruel circumstances. Maximus is no crusader against this disgusting

"sport", he's just an angry and righteous man who hopes to survive long enough

to find justice. There are flickers of thematic resonance, but they're never

pursued beyond minimal suggestion. The "battles" that are waged between the

gladiators are staged more like mini-wars than mano-a-mano struggles, which–particularly

when Maximus rises to the occasion and asserts himself as a leader for his "team"–suggests

that his job hasn't really changed much, except that now he's leading battles

merely for the immediate pleasure and amusement of the citizens he used to serve

in the field. The moment resonates a bit, because Marcus Aurelius had earlier

lamented that his popularity with Roman citizens was largely earned through

the reflected glory they felt from his conquests. Scott has no interest in examining

the nature of this blood-lust, however. It is shown, but not in a revelatory

way. As for the issues addressed in the political goals of Maximus (restoring

the Republic), they never rise to the level of passionate importance for the

audience, because Maximus is motivated more by his loyalty to the dreams of

his dead Emperor than by any personal passion he feels for the issue itself.

If it weren't for the fact that Commodus is so obviously ill-suited to ruling,

we probably wouldn't care at all about restoring the Republic.

Unlike

Spartacus, which concerned itself with the many ways that such slavery

was both deadly and–even in survival–a fate worse than death, Gladiator

contents itself with mourning the unfairness of this one man's fall into such

lowly and cruel circumstances. Maximus is no crusader against this disgusting

"sport", he's just an angry and righteous man who hopes to survive long enough

to find justice. There are flickers of thematic resonance, but they're never

pursued beyond minimal suggestion. The "battles" that are waged between the

gladiators are staged more like mini-wars than mano-a-mano struggles, which–particularly

when Maximus rises to the occasion and asserts himself as a leader for his "team"–suggests

that his job hasn't really changed much, except that now he's leading battles

merely for the immediate pleasure and amusement of the citizens he used to serve

in the field. The moment resonates a bit, because Marcus Aurelius had earlier

lamented that his popularity with Roman citizens was largely earned through

the reflected glory they felt from his conquests. Scott has no interest in examining

the nature of this blood-lust, however. It is shown, but not in a revelatory

way. As for the issues addressed in the political goals of Maximus (restoring

the Republic), they never rise to the level of passionate importance for the

audience, because Maximus is motivated more by his loyalty to the dreams of

his dead Emperor than by any personal passion he feels for the issue itself.

If it weren't for the fact that Commodus is so obviously ill-suited to ruling,

we probably wouldn't care at all about restoring the Republic.

Wisely,

Scott saves the best visuals for the last third of the film, helping to retain

our interest in spite of the running time and the somewhat skimpy level of engaging

subtext.

Wisely,

Scott saves the best visuals for the last third of the film, helping to retain

our interest in spite of the running time and the somewhat skimpy level of engaging

subtext.