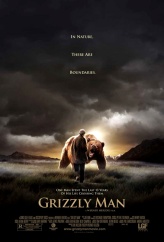

Grizzly Man |

| |

|

Spanish language. Mexico/Ecuador, 2004. Rated R. 108 minutes.

Featuring:

Timothy Treadwell, Werner Herzog, Jewel Palovak, Amie Huguenard, Marc Gaede, Larry Van Daele

Editor: Joe Bini

Original Music: Richard Thompson

Cinematography: Peter Zeitlinger, Timothy Treadwell

Producer: Erik Nelson

Director: Werner Herzog

LINKS

|

he food chain could be described as the organizing structure of the Earth's ecosystem. Predators feed on the weak and fear the strong. In North America, there are no predators larger or stronger than the Kodiak grizzly bear. It is ill-advised to approach one without the protection of an armored truck. Native Alaskans have always respected the grizzly, and kept their distance. One non-native named Timothy Treadwell thought he could befriend them with a garland of good intentions, deter their attacks with stern reprimands, and cohabitate with them in harmony.

he food chain could be described as the organizing structure of the Earth's ecosystem. Predators feed on the weak and fear the strong. In North America, there are no predators larger or stronger than the Kodiak grizzly bear. It is ill-advised to approach one without the protection of an armored truck. Native Alaskans have always respected the grizzly, and kept their distance. One non-native named Timothy Treadwell thought he could befriend them with a garland of good intentions, deter their attacks with stern reprimands, and cohabitate with them in harmony.

He got eaten, of course.

Before that happened, though, Treadwell lived with the grizzlies unarmed for thirteen summers. He only died when he took an even more unnecessary risk, staying too late in the year, when grizzly staples like salmon become scarce.

Timothy Treadwell and Amie Huguenard pose for a photograph at the beginning of their final trip into the wilderness in Grizzly Man. |

In those years, Treadwell spent his offseasons educating schoolchildren, making television appearances (including on David Letterman), co-authoring a book, and dedicating his whole life to grizzly preservation. During his last five summers with the grizzlies, Treadwell shot over one hundred hours of footage, which he hoped to turn into a documentary. German filmmaker Werner Herzog (Heart of Glass; Aguirre, The Wrath of God; Nosferatu the Vampyre) has shouldered that task, assembling the tediously over-narrated but otherwise fascinating Grizzly Man, largely from Treadwell's footage.

Grizzly Man offers a complex portrait of a gentle and good-hearted self-styled crusader, but also of a vain, deluded man who threw his life away for nothing. Treadwell fashioned an elaborate personal mythology, in which he characterized himself as venturing alone in the Alaskan wilderness and taking awful risks for the sake of the bears. He saw himself not just as an educator and conservationist, but also as the grizzlies' personal protector against hunters. However, most of the land where Treadwell spent his time is a federally protected reserve where the grizzlies are rarely in danger from humans. The one time he does encounter possible poachers, he hides behind the underbrush without announcing himself, and then interprets a pile of rocks they leave behind as a dire warning directed at himself.

Thus Treadwell inadvertently reveals himself to be both somewhat paranoid and an inveterate liar. Though he claims to be alone with the bears, he was usually accompanied by a girlfriend. The last of these was Amie Huguenard, who died with Treadwell in 2003. Preserving the illusion of solitude, she appears exactly twice in Treadwell's footage, and only fleetingly. Grizzly Man reveals that earlier in life, Treadwell would also invent or exaggerate stories about himself, once claiming to be an orphan from Australia. About the only thing Treadwell didn't lie about was the danger he faced. Grizzly Man opens with Treadwell describing his eventual fate. He excitedly describes the possibility of becoming grizzly lunch so many times that you suspect Treadwell of actually taking his safety for granted. He draws attention to the risk only to represent himself as a courageous adventurer.

Treadwell's personal oddities and inconsistencies pack the film, sometimes to humorous effect. He talks about how “the kind warrior” (himself) must become “the samurai” in order to face down an overly curious grizzly. This is done by making the bear somehow believe you are more powerful. Yet Treadwell warding off a massive grizzly by feebly shouting at it in his effeminate voice does not cut what you would call a fearsome figure. In a letter, Treadwell writes about mutating into a wild animal, but the truth is he has no idea what wild is, not when he's naming the grizzlies things like “Mr. Chocolate” and “Rowdy the Bear.” As a bear biologist comments, it is a simpler world, but also a harsh world. Treadwell never seems to grasp this fully, and certainly doesn't respect it.

Timothy Treadwell talks about bears in footage he planned to make into his own documentary in Grizzly Man. |

Other highlights of Grizzly Man include Herzog's interviews with Jewel Palovak, a close confidante of Treadwell who co-wrote Among Grizzlies. It's obvious she loved him deeply, yet her strange pleasure at receiving Treadwell's wristwatch, recovered from his dismembered hand and still running, is more than a little bizarre. Huguenard, on the other hand, remains an enigma. Grizzly Man is able only to reveal a final act of selfless courage. Treadwell and Huguenard's deaths were captured on audio (the switched-on videocamera still had its lens cap in place, thankfully). Though Herzog declines to include the recording in Grizzly Man, he reveals that instead of running away, Huguenard tried to fight the bear off Treadwell with a frying pan for several minutes before losing her own life.

The evocative footage of the Alaskan landscape, the grizzlies, and several gorgeous foxes befriended by Treadwell serves as a counterpoint to his complicated psyche and disturbing fate. When one fox mischievously steals Treadwell's cap, he is amusingly not amused, and gives ineffectual chase.

It would have been far better for Grizzly Man if Herzog had chosen to allow such moments to speak for themselves. Treadwell and his friends provide all the commentary you need. Instead, Herzog helpfully informs you in voiceover that in Treadwell's footage he found a story of “astonishing depth.” He talks about how much he identified with Treadwell as a filmmaker, because he captured glorious moments “such as studio directors never dream of.” He later relates how a particular “landscape in turmoil” (a glacier) seems to him a metaphor for Treadwell's soul. Herzog goes on and on about “the mysterious beauty” of certain moments instead letting the moments be mysteriously beautiful on their own. Is it really necessary to tell us he cannot perceive anything in a grizzly's eyes other than cold indifference, when a grizzly's cold, indifferent eyes are right there in the middle of the screen?

Herzog basically never shuts up. When he rambles about the “inexplicable magic

of cinema,” he becomes a distractingly pompous twit. He is so busy telling us

about his emotional journey that he makes it impossible for you to have your

own. That doesn't occur to him though, because Herzog is far too occupied with

inserting himself into the film. Particularly galling is his handling of the

recording of Treadwell and Huguenard's demise. Herzog cynically stages a scene

in which he listens to it, making an unconvincingly melodramatic show of being

deeply affected. Then he pleads with Jewel Palovak to destroy the recording.

A reasonable enough sentiment, had he not just tried to titillate you with it,

or at least arouse your curiosity.

It's difficult to call such a foreseeable death a tragedy, but by the end of

Grizzly Man it seems like a part of a larger tragedy. Treadwell was obviously

a deeply troubled, repressed individual whose extreme misanthropy had deep roots

left largely unexplored in the film. Treadwell's whole life was the tragedy,

and his death the product of numerous variables, not just stupidity. As Herzog

closes the film by telling us what truths he thinks emerge from the many hours

of Treadwell's video footage, one truth does emerge. Herzog talks too much.

He comes across as the worst kind of cinematic jackass—the filmmaker who doesn't

trust his own work to speak for itself.

Review © September 2005 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images © 2005 Lions Gate Films. All Rights Reserved.