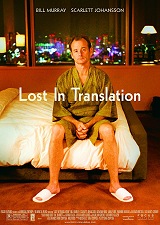

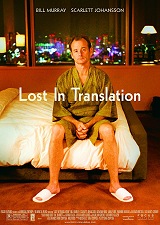

| Lost in Translation |

| |

|

USA, 2003. Rated R. 105 minutes.

Cast:

Bill Murray, Scarlett Johansson, Giovanni Ribisi, Anna Faris

Writer: Sofia Coppola

Original Music: Kevin Shields

Cinematography: Lance Acord

Producers: Sofia Coppola, Ross Katz

Director: Sofia Coppola

LINKS

|

aahhh.

aahhh.

It's been months and months, seemingly, of mindless action movies, sequels,

and mindless action-movie sequels. The summer movie season gets longer and longer,

while most intelligent, adult-oriented movies are now crammed into a three-month

oasis at the end of the year. But it's time to rejoice. The Fall movie season

has arrived, and the first Fall movie of 2003 is writer/director Sofia Coppola's

Lost in Translation.

Lost in Translation is a film about a bond that forms between two people

who find each other in the extremely unfamiliar, culturally alien environment

of Tokyo, Japan. Nothing more, and nothing less. Lost in Translation

tenderly examines that bond, in minute detail.

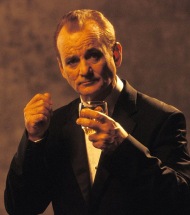

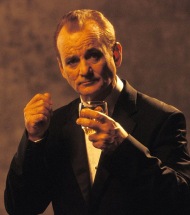

Bill Murray, though he goes by the not-so-very-different name of Bob Harris,

plays essentially himself. His character is a faded middle-aged star who worked

a great deal in the Seventies and Eighties—in one scene we even see a young

Bill Murray on television dubbed into Japanese—but doesn't work quite so

much now. He also happens to be a very good golfer.

Bob doesn't appear to lack for money, but his fame and earning power have eroded,

and so he accepts a whiskey endorsement gig in Japan, one that will pay him

two million for just a week of work. As product endorsements don't carry the

same "sell-out" stigma in Japan that they do here, this is not an uncommon phenomenon.

Would Harrison Ford do a beer endorsement in the United States? No, but he has

done it in Japan. Coppola may even have been thinking of Orson Welles, who himself

was reduced to doing a television commercial for a Japanese whiskey not long

before he died.

Though Bob does not enjoy the gig, he has resigned himself to it. He is similarly

resigned to his longtime second wife with whom he no longer shares much of anything.

She never tires of trying to guilt-trip him for not being home, while not caring

in the slightest what Bob might be doing or experiencing half a world away.

When he talks to her, he says nothing of substance, feeding her only the falsely

upbeat twaddle he thinks she wants to hear, copiously sprinkled with the word

"great."

As Bob, Murray exudes quiet, mundane tragedy. The man who once stole every

film he did, bending it to his comic will, tranquilly inhabits Lost in Translation,

serving the larger work instead of himself, as he did in Rushmore.

Murray's sense of humor has not changed, but understatement is his tool now,

and he's funnier than ever he was in Meatballs, Caddyshack, or Ghostbusters.

He has the unparalleled ability to draw attention to the absurdity of any situation

with just a slight facial movement, and to punctuate it gently with a laconic

deadpan line, without stepping outside of his character's melancholy.

Coppola gives him abundant opportunities to employ this talent, as he contends

with his garrulous commercial director's ridiculous instructions and the interpreter's

improbably concise translations, or when he reacts to enthusiastic Americans

who recognize him by merely walking away. Murray doesn't say anything,

but we know what he's thinking. His struggle to understand his peculiar complimentary

prostitute, courtesy of the whiskey company, is one of only a few moments of

overt, flat-out farce.

"For a relaxing time, make it Centauri time." |

Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson of Ghost World

and The Horse Whisperer) is the other main character. A recent philosophy

major, unemployed of course, she is in Tokyo with her mostly absent photographer

husband (Giovanni Ribisi), who has come to Japan to work. Like Bob, we hear

her describe things as being "really great" and not meaning it. "I don't know

who I married," she confesses early on. We see evidence of this when they encounter

a bubble-headed American star (Anna Faris) with whom her husband has worked

before. Shocked by his obsequious behavior, Charlotte looks at him as if he's

gone insane. His response is to accuse her of being a snob. Charlotte is lost,

and her CD of "A Soul's Search" isn't helping any.

Both Bob and Charlotte feel disconnected from the world they live in, including

their spouses. Their dislocation in Tokyo merely underscores an already existing

situation for both of them. Suffering from jet lag, they keep bumping into each

other at odd hours in various parts of the hotel. As their bantering acquaintance

blossoms into a friendship, they become conspiratorial kindred spirits in an

alien world and begin to share their innermost feelings. "I'm stuck. Does it

ever get easier?" Charlotte wants to know. Bob tells her that the more you know

who you are and what you want, the less upset you get at things. But does he?

It doesn't seem like he knows what he wants; it seems only that he's not getting

upset anymore. Less accepting, Charlotte is too young to have become desensitized.

Bob talks about organizing a "prison break" out of the hotel, but it is Charlotte

who finally tugs them both into the world outside—a world whose strangeness

has created and nurtured a friendship that might otherwise have never existed.

Coppola has made an intimate and beautifully modulated film. Coppola's unusual

opening shot bespeaks the intimacy of the film. It is a close-up of pink panties,

seen from behind, worn by a woman lying in bed on her side, who turns out to

be Charlotte. It is not a sexual image—the lens is soft and the lighting

dim. This is typical of Lost in Translation. Though it observes two characters

sharing a very private interaction—one that does not fit easily into the

rest of their lives—it does so from a distance, as if through a veil or

as something remembered rather than directly experienced. Coppola has said that

she wanted the film to look like a memory, and it does. She specifically avoided

using digital video, favoring the softer look of film. Much of the movie is

shot at night or indoors. The brighter scenarios—the daytime panorama of

Tokyo, or the city's circus of nighttime advertisements—are shot through

windows, muting the brilliance. The technique has a distancing effect, making

it feel like the events are happening on the other side of the world, which,

of course, they are.

Coppola has a similarly subdued approach to the comedy. When Bob struggles

with an exercise machine happily chirping instructions to him in Japanese, Sofia

Coppola does not use close ups or accent the scene with musical cues. She just

sets the camera down a few yards away and matter-of-factly observes. In another

scene, Bob and Charlotte watch a movie in a language they don't understand (Italian),

subtitled in another language they don't understand (Japanese). The comedy is

frequent, but rooted in plausible situations.

Though the story is not rushed, the film is devoid of filler. Coppola has the

intriguing habit of cutting away in the middle of a scene. Once the event is

established and she has communicated what she wants, she doesn't waste time

following the scene to its natural conclusion. In the case of the funnier scenes,

doing so would only belabor the humor. Coppola just moves on, as, eventually,

Bob and Charlotte must also move on. Their stay in Japan is finite. As the end

looms, the pressure to determine what their bond means grows. What is it, exactly?

Is it destined to be just a momentary connection? Can it be taken back home

to the United States, or would it just get lost in the transplantation?

A note about the ending

This note contains spoilers. It is intended for readers who have

already seen the film.

If there is anything to complain about in this sublime film, it is the conclusion.

Coppola goes for an open ending, which is not in itself a problem. Many films

choose not to resolve their conflicts; if the characters are transformed, that

is sufficient. However, Lost in Translation is about a clearly defined

period of time in a foreign environment. with a natural ending point. As Lost

in Translation approaches that point, Charlotte needs Bob to acknowledge

that their connection is more than a simple friendship, even if it is less—as

it must be—than a romantic affair. They may never see each other again,

but they have changed one another. Bob finally understands what Charlotte needs

and catches her before heading to the airport. "I don't want to leave," he announces

awkwardly, suggesting he knows their friendship could not be the same back home.

He then whispers for a few moments in her ear, gives her a chaste but lingering

kiss on the mouth, and leaves. We cannot, however, hear what Bob says.

Does Bob admit to stronger feelings for Charlotte? If so, what kind of feelings?

Does he suggest they see each other again? We can see that Bob offers Charlotte

some kind of resolution, but we don't know what. On the one hand, Coppola's

choice allows us to speculate, to decide for ourselves what it all means. On

the other hand, isn't this lazy screenwriting? Is she afraid to let us hear,

or just being excessively arty? By explicitly withholding Bob's words, it's

as if she is saying, "Ha-ha, I know a secret, and I'm not telling."

She is too obvious about the fact that she's being ambiguous. It's a slightly

dissatisfying finish to an otherwise perfect film.

Review

© September 2003 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images © 2003 Focus Features. All Rights Reserved.