| Luther |

| |

|

Germany, 2003. Rated PG-13.

Cast:

Joseph Fiennes, Peter Ustinov, Alfred Molina, Claire Cox, Jonathan Firth,

Bruno Ganz, Uwe Ochsenknecht, Mathieu Carrière, Marco Hofschneider, Torben

Liebrecht, Jochen Horst, Benjamin Sadler

Writers: Bart Gavigan and Camille Thomasson, based on the play

by John Osborne

Original Music: Richard Harvey

Cinematography: Robert Fraisse

Producers: Brigitte Rochow, Christian Stehr, Alexander Thies

Director: Eric Till

LINKS

|

ike

it or not—and a lot of people don't—Martin Luther is the most important

religious figure of the last thousand years, or since Mohammed. The father of

all Protestant faiths, Luther set in motion the Reformation when, as a young

priest and theology professor in 1517, he nailed his Ninety-Five Theses denouncing

Papal abuses to the door of the Wittenberg Church. Allegedly nailed, anyway.

ike

it or not—and a lot of people don't—Martin Luther is the most important

religious figure of the last thousand years, or since Mohammed. The father of

all Protestant faiths, Luther set in motion the Reformation when, as a young

priest and theology professor in 1517, he nailed his Ninety-Five Theses denouncing

Papal abuses to the door of the Wittenberg Church. Allegedly nailed, anyway.

However disseminated, his Theses and other writings represented a simple stand

of conscience that set in motion ecclesiastical revolutions and civic upheavals

resulting in church schisms and utterly changing the political landscape of

Europe. Prone to depression, Luther admitted to struggling throughout his life

with evil spirits and the devil. He was particularly appalled by the violence

that resulted from his stand, particularly the slaughter of 100,000 peasants

after he urged the German princes to restore order. Because of these misgivings

and his plain doctrine that Christ is found in the Gospels, only the Gospels,

and not through intermediaries like the Pope, he steadfastly resisted attempts

to turn him into a saint and an icon.

Ralph Fiennes would be an ideal choice to portray this man. Few actors do the

tormented soul thing better, as The End

of the Affair, The English Patient, and even Schindler's

List attest. In the right roles, Fiennes is an electric performer, opening

windows into his character's inner shadows without falling prey to exaggeration.

Fiennes would be an incandescent Luther.

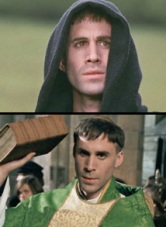

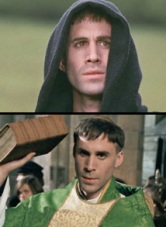

Unfortunately it is not Ralph Fiennes who plays Luther, but his younger brother

Joseph. He wears a constant expression for much of the film: a slight frown

above a set mouth, with his large, dark eyes focused on a point about four feet

in front of him. Pain? Slight frown, set mouth, eyes focused four feet in front

of him. Shock? Slight frown, set mouth, eyes focused four feet in front of him.

Conflicted distress? Slight frown, set mouth, eyes focused four feet in front

of him. As Luther, Joseph Fiennes is merely adequate. With his smoldering dark

looks, he can portray a certain romanticized anguish, but lacks the chops to

make the performance transcendent.

Joseph Fiennes stars as Martin Luther |

In addition to a transcendent performance, Luther could have used a

more focused script. A concise screenplay that distills the essence of Luther's

life coupled with a little experimentation could have made Luther into

a stirring affirmation of faith akin to, say, Martin Scorcese's religious films

(The Last Temptation of Christ and Kundun). There are certainly

parallels to the life of Christ. Luther's visit to Rome recalls Christ's visit

to the temple in Jerusalem when he expelled the moneychangers. The times Luther

wrestles with himself alone in his cell recalls similar scenes in Last Temptation

of Christ, as does Luther finally shedding his religious garb and marrying.

Director Eric Till doesn't push the Christ angle, though, and Luther himself

would no doubt have been appalled if he had.

Instead, Luther goes the standard bio-pic route, and suffers from bio-pic-itis

as a result. What is bio-pic-itis? It is when, in an attempt to be comprehensive

and faithful to a person's life, a movie crams in a whole bunch of information

and events at the expense of coherent thematic delineations, a central organizing

principle, and depth.

None of this is to say that Luther is a bad film, just a slightly disappointing

one given the meaty subject matter. It's tremendously informative, for instance,

if it is possible to judge movies by such a standard. We see all the major events

of Luther's life—his vow to devote his life to God during a violent thunderstorm,

his entry into the order of the Augustinian Hermits in Erfurt, his joining the

faculty at Wittenberg University, his campaign against the Church's sale of

indulgences (which supposedly assured a place in heaven for the purchaser, or

a relative), the pressure on him to recant and his appearance before the Imperial

Diet of Worms in 1521, his excommunication, and his translation into the German

vernacular of the scriptures, which were previously inaccessible to common people

by the Church's design. It is astounding to think about the kind of ignorance

and docility people must have lived in to accept the abuses foisted on them

by the Church in those times.

It is also troubling what is not touched on in the film, such as Luther's virulent

anti-Semitism, which was commonplace at the time but disturbing nonetheless.

On Jews and Their Lies, which Luther wrote in 1543, is a vile, vituperative

document in which he excoriates the Jews for pride and racism while exhibiting

the same traits. (To be fair, he also produced conciliatory works like Jesus

Christ Was Born a Jew.)

The superficiality necessitated by such a full script means a nagging lack

of understanding of the German princes' motives in supporting Luther and defying

their emperor, Charles V (Torben Liebrecht), particularly those of Frederick

the Wise (Sir Peter Ustinov), who positions himself as Luther's protector while

subtly defying the Emperor he strongly fears. Similarly, Luther does

not clearly show how and why Luther urges the princes to suppress the rebellions

sparked by his writings and led by his former university colleague Carlstadt

(Jochen Horst). We see only his shock beforehand and guilt at the subsequent

death toll.

It is not fair, however, to characterize Luther as a pedestrian recitation

of events. Sprinkled throughout the film are distinctive moments that hint at

the passion and otherworldliness that we would expect at the heart of such a

story. The thunderstorm at the beginning of the film, for example, when Luther

is almost struck by lightning. The way an overwhelmed Luther's hands shake at

the first Mass he gives, causing him nearly to drop the bread and wine. The

light of the outside sky replacing the head of the Madonna when a rock is thrown

through a stained glass window.

Luther is further strengthened by the uniformly solid supporting cast,

with Ustinov lending his character a depth not fully written into the script,

and Bruno Ganz expressively representing the troubled affection Johann von Staupitz

feels for his protégé in the Augustinian Hermits. Claire Cox makes a strong

Katharina von Bora (Luther's eventual wife), in contrast to Liebrecht, who makes

a suitably weak Emperor. As the villains, Uwe Ochsenknecht (playing Pope Leo

XII) and Jonathan Firth (the Pope's underling Girolamo Aleandro) are distasteful

without being cartoonish, while Alfred Molina appears in a too-small role as

indulgence-vendor Johann Tetzel, with his absurd rhymes—"When a coin in

the coffer rings, a soul from Purgatory springs!" Finally, the score is unmemorable

but well chosen orchestral music with pipes and other instruments that effectively

evoke the period.

The bottom line is that Luther is a reasonably solid account of a fascinating

figure's life that leaves an audience wishing for more—or less. More running

time, to tell the story better and fully understand all the characters, the

kind of time that a television miniseries could provide. Or less story, to concentrate

less on events and more on Luther the man, who he was and why he told the world,

as legend has it, "Here I stand. I cannot do otherwise."

Review

© September 2003 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images © 2003 RS Entertainment. All Rights Reserved.