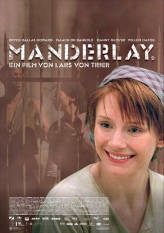

| Manderlay |

| |

|

Denmark/Sweden/Netherlands/France/Germany/USA, 2005. Rated R. 133 minutes.

Cast:

Bryce Dallas Howard, Danny Glover, Isaach De Bankolé, Willem Dafoe, Lauren Bacall, Michaël Abiteboul, Jean-Marc Barr, Geoffrey Bateman, Virgile Bramly, Ruben Brinkman, Dona Croll, Udo Kier, Jeremy Davies, Llewella Gideon, Mona Hammond, Ginny Holder, Željko Ivanek, Chloë Sevigny, John Hurt (narrator)

Writer: Lars Von Trier

Original Music: none

Cinematography: Anthony Dod Mantle

Producer: Vibeke Windeløv

Director: Lars Von Trier

LINKS

|

hen I wrote about Lars Von Trier's Dogville, shot largely on a bare soundstage, I criticized it for being an intentional denial of those things that make cinema a unique form of art. I also called Dogville the most self-important, heavy-handed film in recent memory. That's not true of Manderlay. It's only the most self-important, heavy-handed film since Dogville.

hen I wrote about Lars Von Trier's Dogville, shot largely on a bare soundstage, I criticized it for being an intentional denial of those things that make cinema a unique form of art. I also called Dogville the most self-important, heavy-handed film in recent memory. That's not true of Manderlay. It's only the most self-important, heavy-handed film since Dogville.

For those of you looking for a movie recommendation, let's get it out of the way. If you liked Dogville, go see Manderlay . If you hated Dogville, treat Manderlay as if it has ebola, the bird flu, and the bubonic plague combined.

Dogville functions on two levels—as a comment on both U.S. internal affairs and U.S. foreign policy. Through his “sad tale of the township of Dogville,” Von Trier pontificates, for example, about the treatment of immigrants. The film's conclusions could apply equally to any rich country, but of course the dogme filmmaker insisted Dogville is about the United States. Manderlay, the second film in Von Trier's “American Trilogy,” also functions as a comment on both internal and external U.S. affairs. Now Von Trier addresses race relations. At the same time, he strongly criticizes American interventionism, particularly in Iraq.

Here Von Trier uses the same protagonist as Dogville, Grace, but gives us a new actor to fill her shoes—The Village's Bryce Dallas Howard. She's a much younger Grace than Nicole Kidman's version (even though Manderlay takes place after Dogville), and a far less likeable one. Whereas Kidman's Grace was a self-sacrificing victim for most of the film, Howard's Grace perpetrates many injustices through her stupid, stubborn idealism.

Bryce Dallas Howard lectures on democracy in Lars Von Trier's Manderlay. |

It's the 1930s. Grace, her father (Willem Dafoe, replacing James Caan), and his band of gangsters happen upon a Southern plantation where slavery still exists. In a highly improbable turn of events, Grace persuades her father to give her a handful of men and even a lawyer to take over the plantation. They sweep aside the overseers and impose democracy by force faster than you can say “Baghdad.” Grace assumes control with the best intentions, but her naiveté is monumental. She believes freedom will bring about a change in character, and soon the former slaves are voting on everything, including what time it is. Under Grace's blundering leadership, the plantation soon experiences one disaster after another.

Howard is a much more photogenic Commander-in-Chief than George Bush, but there's no question who she is supposed to represent, and there's no question what Von Trier is saying about Iraq. With regard to racial dynamics within the United States, Manderlay's conclusions are more ambiguous. One message is quite clear, though. People have to liberate themselves. You cannot do it as an outsider, particularly as an ill-informed outsider. That might be true, even though the use of that rationale to stand aside and do nothing during genocides in places like Bosnia or Rwanda is worrying.

The problem with Manderlay is not with what it has to say. Even if you don't like it, you can't judge a film solely by whether you agree with it. The problem is with how Manderlay says what it has to say.

We could get into the film's use of and comments about racial stereotypes, including Danny Glover's house slave and Isaach De Bankolé's proud n—well, you get the idea. We could discuss what it means that Grace keeps getting raped, and whether Grace's wild sexual fantasies with black men, described in detail by John Hurt's narrator, are offensive. It's shameful that Von Trier would include certain things, but nothing gets in between him and hammering home a point.

Whether Von Trier is qualified to hammer home those points is also problematic. There is something to be said for the perspective of a third-party observer with the benefit of a little distance. However, one cannot understand race relationships in the United States based on the photos and lectures of Jacob Holdt, no matter how good or illuminating those photos and lectures may be. You might even point out that Europe, including Von Trier's native Denmark (which made huge profits off the slave trade), is complicit in everything the United States has done and currently does, and that it has its own race problems.

You could say such things to discredit Von Trier, but none of that necessarily means what he says is not valid, and none of that gets to why Manderlay fails. Manderlay fails because it is, like Dogville, just an intellectual exercise. It is too obviously a filmmaker's construct designed to send a message, and because of that, the message is undermined.

Regardless of whether you agree film should deliver political and moral messages, those messages are always more effective when the story works. You have to show that what you have to say is true. The truth must be felt in the realistic behavior of well-drawn characters, and in the story developments they set in motion. It's not enough just for a filmmaker to say, “This is true.” Audiences come to feel that a message is true when everything else about the film feels true. Even science-fiction must have plausible characters and organic plots.

Manderlay, on the other hand, is a didactic, dare I say, dogmatic film that is nothing more than a filmmaker lecturing his audience. Within its bare-soundstage production gimmick, its stereotypical characters, and its implausible story developments, Manderlay is too artificial to feel true.

When I critiqued Dogville, I wrote:

Von Trier has constructed the whole story solely to make a point, which undermines the conclusions Von Trier wants you to draw from it. The conclusions, no matter how legitimate they may seem, are based on an artificial model designed to lead you to those conclusions. In formal logic, they call that a tautology.

All that applies to Manderlay, and no doubt will apply to the third film in Von Trier's American Trilogy, which will be called Washington.

[Read the AboutFilm interview with Bryce Dallas Howard]

Review

© January 2006 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images © 2006 IFC Films. All Rights Reserved.