The Merchant of Venice

aka William Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice |

| |

|

USA/Italy/Luxembourg/UK, 2004. Rated R. 138 minutes.

Cast:

Al Pacino, Jeremy Irons, Joseph Fiennes, Lynn Collins, Zuleikha Robinson, Kris Marshall, Charlie Cox, Heather Goldenhersh, Allan Corduner

Writers: Michael Radford, based on the play by William Shakespeare

Original Music: Jocelyn Pook

Cinematography: Benoit Delhomme

Producers: Cary Brokaw, Michael Cowan, Barry Navidi, Jason Piette

Director: Michael Radford

LINKS

|

" ords, words, words..." screams Eliza Dolittle at the doltish Freddy Eynsford-Hill in My Fair Lady, ”I'm sick of words. Show me!" Ah, the direct entreaties of the frustrated; I sympathize, Eliza, I really do. At least I did, when I was studying Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice in high school.

ords, words, words..." screams Eliza Dolittle at the doltish Freddy Eynsford-Hill in My Fair Lady, ”I'm sick of words. Show me!" Ah, the direct entreaties of the frustrated; I sympathize, Eliza, I really do. At least I did, when I was studying Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice in high school.

At the time, the single biggest problem I had studying this play was the lack of film version. Luckier students in the same module the prior year got to have Zefferelli's Romeo & Juliet as a study aid, and those in the year after, Polanski's Macbeth. They also got to have crushes on Olivia Hussey and Francesca Annis in the bargain. Instead, I had to make do with the original text and, luckily, a performance of the play. Well, I say lucky, but I am rather ashamed to admit that when I eventually found myself gawping vacantly at the dark stage upon which some actors were gamely gamboling through The Merchant of Venice, Eliza's thoughts were pretty much my thoughts too. Like your average teenager, I was not well-disposed to the comparatively languorous world of classic literature, particularly an unexpurgated version in a stuffy theater. And as was my wont in the face of the higher arts, I fell asleep. And failed my exam.

Aside from a made-for-TV version in 1973—an adaptation of a National Theatre (UK) production starring Lawrence Olivier as Shylock—no other faithful film version of The Merchant of Venice has ever existed. And, director Michael Radford's effort notwithstanding, nor does one still.

Radford's truncated version of The Merchant of Venice is neither a faithful reading of Shakespeare 's text, nor even a film that successfully stands alone of it. Don't get me wrong, I don't believe that filmmakers should be slaves to complete texts. I love adaptations, and frankly, some of my favorites (BBC productions of Dickens' Our Mutual Friend and Austen's Pride and Prejudice come to mind) would be close to interminable were they not abridged.

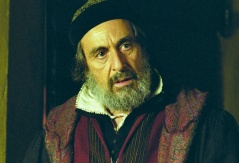

Al Pacino as the bilious Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. |

It is true that Radford (who modestly shares a screenwriting credit with the Bard) has distilled the play into a far more direct story by stripping it of most distracting diversions. But, in spite of the film's successes (and there are a few—the cinematography, the costumes, Jeremy Irons' Oscar-worthy Antonio) it fails because Radford has bound himself too tightly to the narrative, key themes, and character arcs of the original play. Compounding this, Radford has teased from the play's text a striking gay subtext, which is gilding the lily in a play already rife with anti-Semitism, sexual identity issues, and thoroughly unlikable characters with whom empathy is well nigh impossible.

The merchant of Venice is Antonio (Jeremy Irons), who is feeling out of sorts and can't quite put his finger on why. Could it be that all his assets are held in four trading ships currently sailing the perilous seas? Or is it because his swinging, parasitic gadabout lover, Bassanio (Joseph Fiennes) is hankering after marriage to a rich spinster, Portia (the Cate Blanchett-like Lynn Collins) and needs to borrow three thousand ducats with which to woo her? Cash-poor Antonio agrees to borrow the sum from Shylock (Al Pacino), a moneylender in Venice 's Jewish ghetto, who agrees to lend the sum, despite having been spitefully and publicly denounced by Antonio for practicing usury (lending money with interest). The bilious Shylock, sensing a rare opportunity to make his antagonist wriggle on the hook, perversely demands a pound of Antonio's flesh should he fail to repay the money within three months.

With the baleful deal done, Bassanio sets sail for the island upon which Portia is quarantined, held hostage to the clause in her dead father's will dictating that she can only leave once she marries the suitor who correctly guesses which one of three boxes (made of lead, silver and gold) houses her portrait. Unsurprisingly, the mercenary Bassanio chooses correctly and marries her. The ever-sanguine Portia (watching a parade of uncouth German suitors does wonders for one's Zen, apparently) then takes in stride his bombshell that he's in the hole to the tune of three grand, and his mate is going to lose a fatal chunk of his sinewy bod if the debt isn't repaid on time. (Erm, pre-nup, anyone?)

Armed with the sum to be repaid courtesy of his new wife, Bassanio sets sail for Venice , but too late to satisfy Shylock's terms, and finds Antonio in custody for defaulting on the loan. Unbeknown to Bassanio, Portia has in the meantime consulted her lawyer uncle, and disguised as a man, wings her way to Venice to defend Antonio in the famous courtroom denouement.

All of this sounds like good clean fun, but if there's a reason for an R-rating, surely it's in the savage anti-Semitism of this last scene? The anti-Semitism of the play has been discussed ad nauseam, and I am loath to add to the welter of theory. In Radford's film version, however, it's hard not to see the climax as acting out a revisionist crucifixion, with Antonio, strapped to a chair like Jesus to the cross, at the mercy of the law because of a Jew. This time, though, Antonio's supporters use the Jew's own weapon of first resort, the law, to free their savior, and in so doing, reclaim the law as their own, punitively condemn Shylock as inhumane, render him godless, and insist he convert to Christianity. A tidy day's work, and not a drop of blood spilled.

Tidily shot, too, by the cinematographer, Benoit Delhomme, with cold, natural lighting akin to The Girl with the Pearl Earring and In the Name of the Rose, adding convincingly to the sense of place. Radford's sensible dialog tweaks ("glisten" for "glister" for example) that clarify and contextually add etymological depth (judiciously retaining the archaic "tarry" and "soft" for "wait" and "quiet" respectively) also deserve credit. But the whole is not greater than the sum of these parts, and I came away—and remain—unsure of the point of making this particular film adaptation.

I can see none, other than that Al Pacino is apparently The Greatest Film Actor of His Generation and is finally of age to play Shylock and therefore…the film Had To Be Made. Yet his bearded gnashing and spitting, his flailing and simpering, and his seeming inability to act in the same frame as another actor, are not only far from the definitive portrayal I suspect the production craves; they are symptoms of a malaise of mediocrity. Is it unreasonable to reserve lauding an actor until he's actually made eye contact with another and convinced me that he is in and of that moment? Perhaps that's the difference between acting for the stage and acting for the camera? I don't know enough about the craft to say. I do know that I was as enthralled and convinced by Jeremy Irons' finely wrought Antonio as much as I was underwhelmed by Pacino's Shylock. That the film is in thrall to the reputation the latter more than the performance of the former is perhaps its greatest misfortune.

Review

© January 2005 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images © 2004 Sony Pictures Classics. All Rights Reserved.