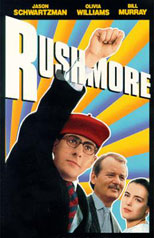

| Rushmore |

| |

|

USA, 1998. Rated R. 93 minutes.

Cast:

Jason Schwartzman, Bill Murray, Olivia Williams, Seymour Cassel, Brian

Cox, Mason Gamble, Sara Tanaka, Stephen McCole, Luke Wilson, Deepak Pallana,

Andrew Wilson, Marietta Marich, Ronnie McCawley, Keith McCawley, Connie

Nielsen

Writer: Wes Anderson, Owen Wilson

Music: Mark Mothersbaugh, Pete Townshend (additional songs)

Cinematographer: Robert D. Yeoman

Producers: Barry Mendel, Paul Schiff

Director: Wes Anderson

LINKS

|

Note: The following commentary contains spoilers.

For a discussion of this film without spoilers, read Carlo's review.

here's

no other movie that plays like Rushmore does. I am most drawn to the

movie because of its singular tone. It could be described as "playful melancholy"--outwardly

funny and absurd, but sad and bittersweet underneath, with a pulse of hope beating

more insistently as it concludes. This tone is conveyed in every facet of the

film: the acting, the direction (by which I mean the montage and frame composition),

the screenplay, cinematography, and music. It's a tone that recreates the contrary

feelings of adolescence: teetering invincibility, boundless optimism and ambition

dogged by defeat, and the swoon of discovering yourself in unguarded moments.

The film celebrates being sadder but wiser, the hallmark of coming of age.

here's

no other movie that plays like Rushmore does. I am most drawn to the

movie because of its singular tone. It could be described as "playful melancholy"--outwardly

funny and absurd, but sad and bittersweet underneath, with a pulse of hope beating

more insistently as it concludes. This tone is conveyed in every facet of the

film: the acting, the direction (by which I mean the montage and frame composition),

the screenplay, cinematography, and music. It's a tone that recreates the contrary

feelings of adolescence: teetering invincibility, boundless optimism and ambition

dogged by defeat, and the swoon of discovering yourself in unguarded moments.

The film celebrates being sadder but wiser, the hallmark of coming of age.

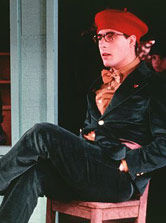

Rushmore's protagonist, Max Fischer, is a child who thinks he's an adult.

In the course of the film, he's expelled from the womb of his surrogate mother,

his school Rushmore, and weans himself of the narcissism that accompanies a

teenage know-it-all. Max doesn't have a real mother; his mother is Rushmore,

and he clings to her because the school provides him with an identity. Coming-of-age

is the process of obtaining a discrete identity not wedded to one's parents,

peers, or school. Max's ties to his school are exceptionally strong. He's involved

in every extracurricular club imaginable (my favorite is the Bombardment Society),

and when asked what his "secret" is, he replies, "I think you just gotta find

something you love to do, and then do it for the rest of your life. For me,

it's going to Rushmore." Excepting the last line, this is the contention of

the entire film--that there are things in life worth having a passion for, and

the meaning we derive from life is a product of these passions.

AboutFilm.Com

The Big Picture

|

| Alison |

B+

|

| Carlo |

C+

|

| Dana |

B

|

| Jeff |

A+

|

| Jen |

B

|

| Kris |

A-

|

| ratings explained |

Writers Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson's genius was to level the playing field

for Max. Instead of pitting Max the teenager against a syndicate of stodgy adults,

the universe of Rushmore is a world where the young and old are on equal

footing. Though at times this strains reality, it's no less real than the countless

films we've seen where generational solidarity is accepted as the norm, and

characters are assumed to think a certain way because they were born in a certain

year. Max is thus able to befriend Rushmore alum Herman Blume (played gracefully

by Bill Murray in a performance that is worthy of Buster Keaton), conduct pow-wows

with the school's dean, and attempt to romance 1st-grade teacher Miss Cross

(Olivia Williams). It is Miss Cross, however, who balks at the evaporated distance

between child and adult. Or, I should more accurately say, it is Miss Cross

who perceives that a fundamental distance still exists. She rightly sees Herman

and Max as the same--little children in adult disguises. It's only when Max

finally discovers himself in a moment of unguarded revelation that he's able

to break free from his downward spiral and help himself and his friend Herman.

That moment of revelation is my favorite scene in the movie. It occurs after

a series of increasingly pathetic attempts by Max to win back Miss Cross. Max

has taken a first step toward growing up by reconciling with his protégé Dirk,

and is outside flying a kite with him. Suddenly, a buzzing remote-control airplane

interrupts his flying, and Max becomes aware of another person sharing the airspace.

It is the Korean girl Margaret Yang (a more adorable character has never existed),

who has been following Max like a puppy dog since he came to her school. She

expresses her exasperation with Max's refusal to acknowledge her existence,

and Max is suddenly struck with guilt and recognition of his immaturity. In

a moment that never fails to catch my throat, Max asks Dirk to take dictation,

"Candidates for the Kite Flying club...Margaret Yang."

Max is out of his slump, but he's not the old Max. He's a restitutive person

who finds a passion in helping others as much as himself. He makes amends with

the school bully by offering him a role in his new play (it turns out the bully

had always wanted to be in Max's plays). More significantly, he gives up the

war over Miss Cross, enabling Herman and her to start anew.  This

is symbolized in the choice of Max's final play, a Vietnam-set production called

"Heaven and Hell." Herman's world-weariness is attributed partly to having been

"in the shit" in Vietnam, and the play is Max's affectionate tribute to Herman

as a friend. The play ends with the hero getting the girl, coupling Max's attachment

to Margaret with Herman's to Miss Cross.

This

is symbolized in the choice of Max's final play, a Vietnam-set production called

"Heaven and Hell." Herman's world-weariness is attributed partly to having been

"in the shit" in Vietnam, and the play is Max's affectionate tribute to Herman

as a friend. The play ends with the hero getting the girl, coupling Max's attachment

to Margaret with Herman's to Miss Cross.

Anderson's cinematic techniques further contribute to the film's unique tone.

His use of widescreen compositions is atypical for a comedy. Usually, a director

just places the action in front the camera and lets the gags fly. Anderson's

compositions are meticulous though, and every shot is carefully composed to

identify the parameters of Rushmore's universe. Characters are rarely

centered in the middle of the frame, leaving an off-kilter and eccentric viewpoint

that isn't static. There is depth-of-field to shots too, as when Bill Murray

hilariously breaks into a sprint after he's shuffled off to the background in

a scene. The width and depth of the frame connote a fulsome world rife with

possibilities. Utilizing the widescreen, Anderson is able to populate his frame

with several characters at once, as in the final scene where young and old alike

are dancing to The Faces' "Ooh la la."

That song is just one of many beautifully employed songs in the film. As The

Faces' chorus of "I wish that I knew what I know now, when I was younger" sounds

over the final scenes, it imparts the playfully melancholic tone I described

earlier. The soundtrack consists largely of British Invasion bands from the

late 60s and early 70s. The music is youthful--at times angrily arrogant, and

other times idealistic and sweet--but because it comes from an older generation

it reinforces the meshing of teen and adult onscreen. It's the words from the

adult generation's teen years commenting wryly on the all-too-familiar events

before them. As the movie's tone darkens and then lifts, so does the music.

Max's turnaround is accompanied by John Lennon's lovely "Oh, Yoko," a song whose

evocation of passion for a subject that gives you life-sustaining force is,

in a nutshell, what makes Rushmore so great.

Review

© May 2001 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images © 1999 Touchstone Pictures. All Rights Reserved.

This

is symbolized in the choice of Max's final play, a Vietnam-set production called

"Heaven and Hell." Herman's world-weariness is attributed partly to having been

"in the shit" in Vietnam, and the play is Max's affectionate tribute to Herman

as a friend. The play ends with the hero getting the girl, coupling Max's attachment

to Margaret with Herman's to Miss Cross.

This

is symbolized in the choice of Max's final play, a Vietnam-set production called

"Heaven and Hell." Herman's world-weariness is attributed partly to having been

"in the shit" in Vietnam, and the play is Max's affectionate tribute to Herman

as a friend. The play ends with the hero getting the girl, coupling Max's attachment

to Margaret with Herman's to Miss Cross.