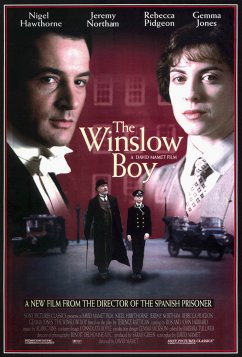

Starring

Nigel Hawthorne, Rebecca Pidgeon, Jeremy Northam, Gemma Jones, Guy Edwards,

Matthew Pidgeon, Colin Stinton, Aden Gillett, Sarah Flind.

Starring

Nigel Hawthorne, Rebecca Pidgeon, Jeremy Northam, Gemma Jones, Guy Edwards,

Matthew Pidgeon, Colin Stinton, Aden Gillett, Sarah Flind. Written by David Mamet based on the play by Terrence Rattigan.

Directed by David Mamet.

Starring

Nigel Hawthorne, Rebecca Pidgeon, Jeremy Northam, Gemma Jones, Guy Edwards,

Matthew Pidgeon, Colin Stinton, Aden Gillett, Sarah Flind.

Starring

Nigel Hawthorne, Rebecca Pidgeon, Jeremy Northam, Gemma Jones, Guy Edwards,

Matthew Pidgeon, Colin Stinton, Aden Gillett, Sarah Flind.

Written by David Mamet based on the play by Terrence Rattigan.

Directed by David Mamet.

Grade: B+

Review by Carlo Cavagna.

Note: This review contains a spoiler. It is clearly marked. If you have not seen the movie, you may want to skip the spoiler.

What kind of a director puts the two most critical scenes--the incident that causes the conflict and the climactic moment--offscreen? Directors just don't do that! Who would have that kind of courage... or bad judgment? David Mamet, that's who. While skipping the two most important scenes would be a catastrophic decision by most directors, for Mamet, it works. It works because Mamet's movies are not about action. He does not use action to further the plot or convey his themes and ideas. Mamet focuses on words. For Mamet, it can be more interesting to talk about an event than to actually see it happen, and in The Winslow Boy, how the events affect the Winslow family is more important than the events themselves.

In pre-World War One London, Arthur Winslow (Nigel Hawthorne) is celebrating

his daughter's engagement when his youngest son, Ronnie (Guy Edwards), arrives

home unexpectedly. Ronnie has been expelled from the Naval College for stealing

and fraudulently cashing a five-shilling postal note. Arthur appeals the College's

decision to no avail, but Arthur will not let the matter rest--even though Ronnie

seems to be perfectly happy at his new school. Arthur and his daughter Catherine

(Rebecca Pidgeon) seek the help of Sir Robert Morton (Jeremy Northam), a prominent

lawyer and Parliamentarian, whom Catherine dislikes because he opposes women's

suffrage.

Because of the human interest element, the case of the "Winslow Boy" soon becomes national news. There is a funny scene in which a reporter arrives at the Winslow residence to conduct an interview, but instead of asking about the facts of the case, she is more interested in examining the fabric of the Winslow's drapes and obtaining a suitably heartwarming photograph of Ronnie.

Lest we think it implausible that a trivial case like that of the Winslow Boy can become the subject of nationwide interest, let us consider what kind of stories make headlines in contemporary America. We eat up stories about Jon Benet Ramsey and Monica Lewinsky and the Kennedys. In The Winslow Boy we even see a political cartoon satirizing the British government for being distracted by the Winslow case, which is not unlike criticisms that the Lewinsky case was distracting Congress from the business of governing the United States.

Despite the media attention, Arthur and Catherine's efforts to clear Ronnie are blocked by one obstacle after another. Yet the case becomes a point of principle to Arthur and Catherine, who are cut from the same cloth. They are proud and stubborn, and will not let the matter lie, even if it means the Winslow's financial solvency and Catherine's marriage.

Though a period movie and Mamet's first screenplay adapted from another work,

The Winslow Boy is unquestionably a Mamet movie. As always, Mamet trusts

in the intelligence of his audience. He refuses to spell things out for us.

For example, he never gives us a definitive answer whether Ronnie is guilty

or innocent. An answer is implied, but Mamet leaves it up to us to decide. Similarly,

Mamet avoids the pitfall of slapping a cheesy romance on the story. [Warning:

spoiler begins here] Although there is obviously sexual tension between

Catherine and Morton, Mamet never allows the tension to bloom into a romance.

At the very end, a beginning of a romance is hinted at, but never shown. Mamet

hints at it only as a sign that, although the case has dramatically altered

the Winslow's lives, and although the outcome of the case is anticlimactic,

the Winslow's lives will indeed go on. [End spoiler]

Of course, the most obvious sign of a Mamet movie is the wall-to-wall verbiage. Like a painter's brush stroke, Mamet's stylized--sometimes stilted--dialogue is what makes his movies distinctive. Rebecca Pidgeon (Mamet's wife) in particular has a peculiar way of speaking that is devoid of inflection. But it suits Catherine's brisk, efficient personality and is quite amusing when she makes a biting remark. Rebecca Pidgeon's real life brother, Matthew, plays Catherine's brother Dickie and contributes an even odder delivery than that of his sister.

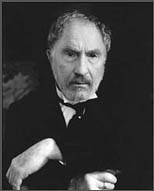

In one of his most assured performances to date, Jeremy Northam is perfect as the arrogant, slightly condescending Morton, and Gemma Jones, as Arthur's wife Grace, is particularly effective in the scene in which she confronts her husband about his true motivations in steadfastly pursuing the case. Hawthorne, however, is the star of The Winslow Boy. His commanding presence dominates the Winslow household, which is appropriate, since it is his strength and pride that propels the story. In his sixties, Nigel Hawthorne (The Madness of King George, Amistad, Richard III, The Object of My Affection, Madeline) is finally achieving wide recognition for his extraordinary acting abilities.

Note: Another film version of The Winslow Boy was made in 1948. Neil North, who played Ronnie in the 1948 version, reappears in the 1999 version as First Lord of the Admiralty.

Review © July 1999

by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Image © 1997 Miramax. All Rights Reserved.

Send us a comment on this review. We'll post a link to the best comments!