Zhou Yu's Train

aka

Zhou Yu de huo che |

| |

|

Mandarin language. China/Hong Kong, 2002. Rated PG-13. 96 minutes.

Cast:

Gong Li, Tony Leung Ka Fai, Sun Honglei, Shi Chingling, Liu Wei, Gao Jingwen, Pan Weiyan

Writers: Sun Zhou, Bei Cun, Zhang Mei

Original Music: Shigeru Umbebayashi

Cinematography: Yu Wang

Producers: Huang Jianxin, Sun Zhou, Bill Kong

Director: Sun Zhou

LINKS

|

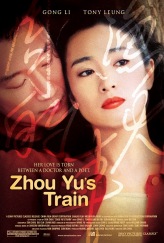

f we all had actress Gong Li's breathtaking face tattooed on the backs of our hands, things like war, famine, and sadness would be impossible. Look at her. You feel somehow better about life, don't you? If you don't now, you will soon—and shame on you for being dead on the inside.

f we all had actress Gong Li's breathtaking face tattooed on the backs of our hands, things like war, famine, and sadness would be impossible. Look at her. You feel somehow better about life, don't you? If you don't now, you will soon—and shame on you for being dead on the inside.

Like many Americans, I first fell in love with Ms. Li, China's most famous and critically hailed actress (she is Alpha and Omega over there), during her performance as a concubine in Raise the Red Lantern. Since then, I have shamelessly loved her as a prostitute in Farewell, My Concubine, an enslaved bride in Ju Dou, and a justice-seeking peasant in The Story of Qiu Ju. You can imagine my excitement at the prospect of loving her on a train.

Much to my surprise, Zhou Yu's Train (the second feature directed by Sun Zhou to star Gong Li) does not really offer up the actress for worship (despite the movie poster). The character of Zhou Yu (Gong Li) is meant to exemplify a more modern version of the Chinese female character—one who follows her own heart in matters of love, instead of being a tragic, beautiful victim of circumstance. Do not get me wrong. Li is still stunning. But in Zhou Yu's Train, Director Zhou wants you to sit up and work for some meaning in every shot—and work HARD.

Sun Honglei and Gong Li in Zhou Yu's Train. |

The film opens as Zhou Yu, a long-haired artisan who lives in Sanming (an industrial village in Northwestern China), runs onto a train carrying a ceramic vase. You hear a male voice reciting poetry that includes the line, “…totally filled by you.” Zhou is headed to the provincial town of Chongyang to visit her lover, librarian and wannabe poet Chen Ching (Tony Leung Ka Fai, not to be confused with Tony Leung Chiu Wai of In the Mood for Love). On her way there, farm veterinarian Zhang Jiang (Sun Hong Lei) offers to purchase the vase. He is also clearly attracted to her. The headstrong Zhou wants none of his advances, and shatters the vase into pieces.

At this exact moment, Zhou Yu's Train narrative also fractures. (And I mean 21 Grams, human-hair-under-a-microscope fractured.) You get the history of Zhou and Chen's courtship in tiny shards. Chen falls for Zhou when he sees her dancing in a club, and is inspired to write. Zhou's love for him grows with his talent, which makes him horribly insecure. The more support she gives him, the more distant he becomes. Nonetheless, she goes to see him twice a week. At each visit, he greets her with a rose. Then, one day, he is not there to greet her. Cut to a little girl dancing. Cut to Zhou and Chen making love in Chen's bedroom, which (via a matte shot) looks like a moving train compartment. Cut to Chen telling Zhou that he is leaving her to take a job in Tibet.

Meanwhile (as if time matters in a film of this sort) Zhang tries to woo Zhou away from Chen, under the guise of becoming her friend. But a real friendship develops. Zhang sees her off on her many trips to the train station. He even follows Zhou to Xan Hu Lake—to which she is compared in one of Chen's poems. When Zhou discovers the lake is not there, Zhang offers, “If the moon can be both round and crescent, then a lake can be empty and full. If it's in your heart, then it's real. If it's not, then it never will be.”

It is clear that Zhang and Zhou are better suited for each other. But Zhou still gets on that damn train, which takes her to Chen and to what she thinks is love. If you are able to piece together their triangle, that is half the battle.

The train serves as both title and motif. You can hear the rocking of wheels over train tracks in every scene, it seems, even the ones where Zhou is painting a canvas or throwing a pot in a kiln. It is as if the film is all a dream you have on one long train ride. Of course, metaphorically, it is. Zhou Yu's “train” is love—its pursuit and experience. It does not matter if you lose it or keep it, if it lasts a day or a lifetime, if it happens in your head or in real life. You need to keep seeking and believing it is there.

Zhou Yu's Train is beautifully shot, and its message is a powerful one. But the director makes an error that renders this already difficult piece downright confusing. While you are trying to work through the metaphorical and confetti-like story, Sun Zhou inserts shots of Gong Li with cropped hair. Because she is alone in most of them, we assume that this is a single and independent Zhou, and that both relationships have ended at some point. But it is not Zhou. Her name is “Xiu.” Once you learn this, you are ready to get off the damn train for good.

I suppose Xiu and Zhou symbolically represent something in the makeup of us all. Exhausted from piecing together the shards of director's shattered “vase,” however, I stopped caring. There is such a thing as too much symbolism, and this guy doesn't know when to stop.

Or maybe I just don't love my Gong Li in short hair.

Review

© July 2004 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images © 2004Sony Pictures Classics. All Rights Reserved.