|

Profile and Interview:

Norman Jewison

by Erika Hernandez

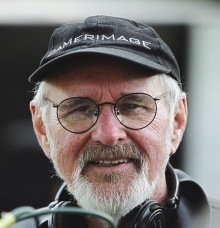

LEFT: Director Norman Jewison on the set of his new film, The Statement .

|

by Erika Hernandez

LEFT: Director Norman Jewison on the set of his new film, The Statement . |

||

![]() orman Jewison has been directing films for several decades. His career longevity, however, should not be ascribed to his directorial genius (at least not in the Kubrick-ian sense). Chocked full of grit, Jewison is more of an enterpriser, and sees his role as director closer to CEO than Artist. This is not to say that he is a hack. When Universal signed this Canadian to a seven-year contract in the early ‘60s, he broke it to direct an MGM project over which he would have more personal control. The film, The Cincinnati Kid, starred Steve McQueen and Edward G. Robinson. Nice move, Norm.

orman Jewison has been directing films for several decades. His career longevity, however, should not be ascribed to his directorial genius (at least not in the Kubrick-ian sense). Chocked full of grit, Jewison is more of an enterpriser, and sees his role as director closer to CEO than Artist. This is not to say that he is a hack. When Universal signed this Canadian to a seven-year contract in the early ‘60s, he broke it to direct an MGM project over which he would have more personal control. The film, The Cincinnati Kid, starred Steve McQueen and Edward G. Robinson. Nice move, Norm.

This decision established Jewison as a risk taker. These risks began to pay off. Perhaps his most critically acclaimed work, In the Heat of the Night (1967) won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Armed with a Best Director nomination, Jewison was sitting on quite a bit of clout. Given America's turbulent sociopolitical environment, though, Jewison took another gamble: he moved to England and directed two musical adaptations of Broadway hits (Fiddler on the Roof and Jesus Christ, Superstar). Even overseas, he earned another Best Director Academy Award nomination (for Fiddler).

Jewison returned to the States in the late Seventies and kept plugging away at various projects, such as And Justice for All (1979), Best Friends (1982), A Soldier's Story (1984), and Agnes of God (1985). In the mood for a romantic comedy (if you have seen Agnes of God, you can sympathize), Jewison then directed the 1987 film Moonstruck. We know what a windfall this was. Cher won her first Oscar, Nicholas Cage carved out a cozy acting niche playing offbeat characters in mainstream films, Olympia Dukakis got a Best Supporting Actress nod, and Jewison sealed his third Best Director nomination. The dreadful comedies Only You (1994) and Bogus (1996) are proof that Jewison needed another serious-themed venture. He delivered with The Hurricane (1999), and attempted another (Dennis Quaid should just not sing, ever) with the cable film/play adaptation, Dinner with Friends (2001).

Amid all of his projects, Jewison founded the Canadian Film Centre in 1988. This successful little institution—established to cultivate Canadian film, television, and new media talent for Canadian audiences—is infused with Jewison's money and abiding energy. Like Jewison, the Centre does not tout lofty, academic philosophies. Its primary concern is to equip its students with the ability to tell “great stories.”

Knowing Jewison's professional history, it is no surprise that his latest project, The Statement, deals with heavy themes, propelled by a “great story.” At a recent roundtable, Jewison discussed working with Michael Caine as Pierre Brossard, a very flawed human whose actions were once inhumane. He also addresses the difference between American and British acting styles, and why he makes films. Be warned, however—Jewison is “in the mood” for another romantic comedy. The question is, are we?

[Read the AboutFilm review of The Statement]

[Read the AboutFilm profile and interview with Michael Caine]

Question: Why did you cast a bunch of English actors in a “French” film?

Jewison: I cast it the same way Polanski cast The Pianist and [Frears] did Dangerous Liaisons and many films because when you deal with a film that takes place in Europe, and you're going to work in English, you'd better work with European actors.

That led me of course to Michael Caine. He's perfect for [this part]. Because Brossard was a young man who was involved with the Milice in 1944 and truly believed he was a French Nazi. And I think all Nazis didn't see themselves as bad people. I've never met a racist yet who thought he was a racist. Or an anti-Semite who thought they were anti-Semitic. I think that's all in the perception of the character. Michael Caine was [also] the perfect age for Brossard. He could play the part of this old man, because we're dealing with an incident that took place in 1944. Secondly there's something common about Brossard. He's small potatoes. He's being manipulated by other people that are much more powerful than he.

Charlotte Rampling and Michael Caine share a quiet moment in The Statement . |

AboutFilm Question: Right, first the Nazis and then the Church—

Jewison: That's right. Well, I mean, the church is his protector in a way.

AboutFilm Question: Is Brossard a rotten human being?

Jewison: Oh, he's a terrible man. He's almost the personification of evil in a way, because he'll do anything to manipulate others. I don't think he's trustworthy. And I think he's betrayed. There's a lot of betrayal in this film, which is my favorite subject, of course. You know, when I read the book, I couldn't talk to Brian Moore because he had died, so I went to his widow, and I said, “Why do I feel at times empathetic in a way to this old guy?” And she said, “Well, Brian always said it's because he's old and it's because what he was involved with was so long ago and he was only part of something, but you're instinctively as human beings, we're always on the side of the animal that's being chased regardless.” So we always seem to be on the side of the rabbit or the fox and not on the side of the hounds.

AboutFilm Question: Nothing speaks to that more than the chase scene when he crawls between buildings, don't you think?

Jewison: Yeah, it's the slowest car chase in cinematic history. People kept saying, “Speed it up, speed it up!” And I said, “No, you don't understand. He's just an old guy!”

AboutFilm Question: So, Caine becomes the personification of the underdog?

Jewison: I guess. There's something kind of likable about him, but at the same time, he does have a dark side that I think is there in Alfie, which is not a very nice person, and Sleuth. Let me give you an example. [In The Statement ], he's sitting in the bar, and he sees somebody pass him and go into the toilet. And he's like an animal. He's very basic. Cunning like an animal, like a fox underground. He sits and he looks and he says, “Can you get out the back?” “No.” And then he says to the bartender, “I have to make another call.” When he said that, the hair on the back of my neck stood up. It was chilling. The son of a bitch, he's gonna kill him! He turned again from the sweet old guy! And he said it so sweetly, and it just scared me.

Question: Did you give Caine much direction?

Jewison: No, at this point in his career. I work with a lot of movie stars, and he's a movie star, but he's also a great actor. I can't say that about every movie star. It's the concentration he has. [He can] transform himself almost immediately, because he fools you. By the time that camera rolls, he's Brossard. But not just acting Brossard. He really is Brossard. Somehow this takes place, [while] there's a lot of American actors I work with who they're in character all day long, and you can't talk to them. They find the inner voice, and it's Method and the whole thing.

With [Caine], and with most British actors—it's amazing. I think they start with the character on the outside and work in. For instance, he talked about his haircut, what kind of haircut does Brossard have? He worried about the haircut, he worried about how he dressed, a cap or so on and so forth.

This material seemed to attract terrific actors. Tilda Swinton, to get her to play the French judge and Jeremy Northam, to get him to play the Colonel. I wanted him desperately to play this part. He's tall, but he's slender and rather aristocratic, and to me he looks like a colonel. He speaks French, so all of the sudden he became very French in his body language and in the pronunciation of certain French words, and Tilda did the same thing. And then to get Charlotte Rampling, I mean come on, I was just so excited. She swept into the hotel in Paris in a fur coat, and I thought, “Jeez, she's never going to play this role.” I'm going to tell her she makes beds in a hotel, and she's going to schlep around in no makeup and her hair with a plastic bag and play Michael Caine's wife. But she did it. She lives in France and she understands the politics, and she wanted to be part of it. I think the scene between them is my favorite scene in the film.

AboutFilm Question: There is a common line uttered by Brossard to Nicole and between the two investigators. And that is—

AboutFilm/Jewison in unison: “Do what you're told, and everything will be all right.”

AboutFilm Question: Right. So, was this intentionally captured in both storylines?

Jewison: I think so. Look, I'm just a storyteller. When I make a film, I never want the film to become a vehicle of social propaganda. If I wanted to do that, I'd make documentaries. So I didn't really—I was more interested in all the research that I did on this film was probably research that Brian Moore had done before he wrote the book, I'm sure.

But what I did find, which really stuck with me was the actual photograph [of the incident]. There were seven bodies lying against a wall with a group or couple of German soldiers, and it was obviously taken in the day. It was maybe the same day that they'd been executed at dawn. That's why I put it at the end of the film. We found the name of every single person, their age, their occupation, and then he went to the wall, and here were seven memorials. We photographed that, too, and put that at the end of the film to remind the audience that this film is about history.

Question: Why was Ronald Harwood right for this?

Jewison: Ronald Harwood was right for the screenplay because I wanted the film to be written by a European. I don't think that a North American writer would give it the right sensibility. Ronald Harwood was perfect. He wrote The Dresser, and he is a brilliant playwright as well as a screenwriter. But he is also Jewish, is from South Africa, he's been living in England, and has a place in Paris. He read the book and loved it. This was before he'd written The Pianist.

Question: Any chance for this film around Oscar time?

Jewison: Oh, I don't know. I have no idea. I don't make films to win prizes. I make films to make films. The distributors worry about that.

Question: What are you doing next?

Jewison: I'm going to do an adaptation of the Italian film, Bread and Tulips. I really like that film. I contacted John Patrick Shanley who wrote Moonstruck. I said, “Look at this film.” We both looked at it, and are going to do an American version of it. We're completing work on the screenplay. I'm in the mood for another Moonstruck experience, for another romantic comedy.

[Read the AboutFilm review of The Statement]

[Read the AboutFilm profile and interview with Michael Caine]

Feature and Interview © January 2004 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images © 2003 by Sony Pictures Classics. All Rights Reserved.

| Related Materials: | ||

| |

||

| |

||

| |

||

| |

||

| |