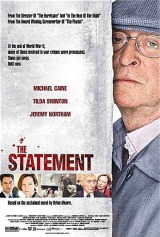

| The Statement |

| |

|

Canada/France/USA, 2003. Rated R. 120 minutes.

Cast:

Michael Caine, Tilda Swinton, Jeremy Northam, Alan Bates, John Boswall, Matt Craven, Frank Findlay, Ciaran Hinds, William Hutt, Noam Jenkins, David De Keyser, John Neville, Edward Petherbridge, Charlotte Rampling, Colin Salmon, Malcolm Sinclair, Peter Wright

Writer: Ronald Harwood, based on the novel by Brian Moore

Original Music: Normand Corbeil

Cinematography: Kevin Jewison

Producers: Robert Lantos, Norman Jewison

Director: Norman Jewison

LINKS

|

Read the AboutFilm profile and interview with Michael Caine.

Read the AboutFilm profile and interview with Norman Jewison.

enerally speaking, we Americans have a one-dimensional perspective on the last gasps of World War II and its aftermath. Hitler committed suicide. Mussolini was lynched by his own people. We dropped the Bomb on Hiroshima. Game over. Our boys came home, our girls got the hell back into the kitchen, and we proceeded to make babies. Lots of them. Genocidal monsters such as Hess and Kaltenbrunner were publicly tried for their war crimes, and the world was left to mourn the victims of their terror.

enerally speaking, we Americans have a one-dimensional perspective on the last gasps of World War II and its aftermath. Hitler committed suicide. Mussolini was lynched by his own people. We dropped the Bomb on Hiroshima. Game over. Our boys came home, our girls got the hell back into the kitchen, and we proceeded to make babies. Lots of them. Genocidal monsters such as Hess and Kaltenbrunner were publicly tried for their war crimes, and the world was left to mourn the victims of their terror.

While we were dizzy with victory, some Nazis and Nazi collaborators (i.e., officers of Axis-occupied countries who killed under their rule) fell through the cracks. Some fled to places like South America and Scandinavia. Others stayed on their native soil. Wherever they went, these guilty little bastards became walking targets for war crime commissioners and extremist groups.

The Statement is set in modern day France, and traces the pursuit of Pierre Brossard (Michael Caine). One night during WWII, Brossard (then a member of France's wartime police, the Vichy Milice) ordered the execution of seven Jews in the town of Dombey. Never prosecuted for this horrible crime, he has been living for the past four decades sheltered by an ultra-conservative faction of the Catholic Church. Until, one afternoon, a man tries to assassinate him. Brossard kills his assailant in self defense, but finds a statement meant for his post-mortem body. Signed by “The Jews of Dombey,” the statement proclaims Brossard's guilt for the executions. Brossard, the walking target, now scurries.

Another threat to Brossard is the new driving force behind his forty year-old legal investigation, Judge Annemarie Livi (Tilda Swinton). Assisted by Colonel Roux (Jeremy Northam), the duo aims to formally charge Brossard with crimes against humanity, and nail anyone who has protected him as accomplices. This quest is especially personal for Judge Livi, who is half-Jewish.

Jeremy Northam and Tilda Swinton are on the hunt in The Statement |

Director Norman Jewison establishes his story at this cat and mouse tempo. When we meet Pierre Brossard, he is running. When we meet Livi and Roux, they are running after him. Okay, there is some buildup. They have lunch first.

While Brossard hops frantically from safe house to safe bar, and from priest to monk to ex-Vichy guy, black and white flashbacks of the Dombey executions are interspersed with shots of present-day Brossard catching his breath. Entirely dependent upon the Catholic Church for food, money, shelter, heart medicine, and salvation, Brossard cannot survive without it. Once Judge Livi and Colonel Roux discover this, they begin to tear it away.

Brossard's eighty year-old jugular is exposed. In time, he will either be starved out or shot outright, which places viewers in a peculiar position. As we are accustomed to empathize with any protagonist, we feel conflicted. Should we root for the capture and death of a guilty man for whom thirty minutes on an uphill treadmill might be lethal? If we want him to get away from would-be assassins or the French government, are we going to hell?

Through most of its narrative, The Statement revolves around Brossard's chase. While the film's chase scenes are realistic (the aging Brossard does not miraculously gain Mission: Impossible strength and speed), they dominate the entire piece. This is an ultimately disappointing choice, for Brossard's character is far more fascinating. Here is a man who, a million years ago, did something unimaginably brutal. He is guilty, but does this make him fundamentally evil? Since he was under orders and has since abandoned his past ideologies in order to survive, might he be—like many “he made me do it” criminals—fundamentally weak?

This debate is never really examined, although we glimpse both sides. Brossard confesses to priests and God constantly, and travels with other symbols of Catholic-tailored guilt and salvation. But does that mean that he is repentant? Or does Brossard cling to any institution that takes him in, whether it be the Nazi Party or the Catholic Church? Could he have turned into a Mormon or a Satanist or an Amway salesman, had they provided him with a monthly stipend, a bed, and his glycerin pills?

Brossard is presented as evil only briefly, when he seeks shelter from his wife, Nicole (Charlotte Rampling). When, where, and how this marriage happened is not addressed, but we know that he bought her a dog she loves very much. He threatens to kill it when Nicole resists taking him in. Cut to them waking up in her bed. This scene gives Brossard's character a stratum of complexity. No time for that, though. He runs again, for “they” are getting closer.

Another odd feature of The Statement is that its principal characters play French citizens, but (as all are Classically-trained British actors) they speak with their native, British accents. This European hybrid intonation works in some places, such as the exchanges between Swinton and Northam's characters. They are first and foremost about the pursuit, and their accents affirm this relationship. Sadly, if they were French, we would more likely be predisposed to think of them primarily as man and woman. The two do have a crisp chemistry, but it is not cultivated in the blatant service of The Statement's plotline.

Although The Statement deals with an intriguing historical phenomenon generally dismissed as a footnote, it is obscured by the film's unceasing chase. Jewison made no misstep in casting Michael Caine as Pierre Brossard. Paradoxically, however, he does not use Caine's talent to its full potential. It would have been something to see what this veteran actor, who has already proven himself in the “cat and mouse” genre, could have done with Brossard's world, had he been perfectly still. It could have been chilling. What makes this killer laugh, for instance? What is his version of normalcy? Can he look into a mirror? Does he go through photos of himself and his comrades in their heyday? Is he outwardly kind to children? This is what we wonder about these men who escaped and lived quietly with their unspeakable actions. Alas, why doesn't our director?

Review

© January 2004 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images © 2003 Sony Pictures Classics. All Rights Reserved.